- Home

- Andre Norton

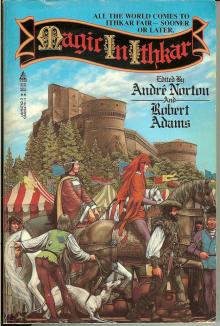

Magic in Ithkar Page 10

Magic in Ithkar Read online

Page 10

For a moment Corielle was tempted to let the pursuit of Lamok go by. Then her anger rose within her as she remembered his smirking pleasure at the many cruelties inflicted on the artisans, officials, and servants left behind in the house. It was he who had decreed that Rumara should be surnamed “the Bastard” and be called nothing else, and smug was his satisfaction at this torment of a small child.

She herself had suffered at his hands, beyond the whipmark, for the wizard had a horse-keeper who tried to show the world he could impose his will on any woman. In those days, Corielle still innocently cried to her lady, even to the interloper’s wife, for justice; but the interloper was the master of his lady, and the wizard was master of the man. They asked Corielle but two questions. “Are you virtuous? Does this man threaten your virtue?”

The smirk on the wizard’s face warned her not to answer as she wished, that her honor was in her own hands, not his, but that he did threaten her person. Instead she answered yes, truthfully, to both questions, and found herself in sudden horror handed over to the horse-keeper as his wife! Which among these people was a brutal bondage indeed. To disobey him, or seem to, meant a beating, and none would defend her; to kill him was to be burned alive. Not even by perfect obedience and walking in fear was she spared, for the horse-master was a cruel and suspicious man who, like his master, delighted in setting traps for the unwary.

But, said the wizard in satisfaction, her virtue had been saved!

Hers was not the only such story; she had seen how the wizard loved to play with people’s lives. She could bring no great charges against him, to hang him, but if she saw him crawling on the ground, she would step on him like the poison roach he was.

Corielle sat shaking as the bitterness of those years came back. “I will go see those priests tomorrow, at first light,” she said. “Rumara, I may not avenge your mother. But it will not be for lack of trying.” She settled her ragged gown around her and began to plan what she was going to say.

She brought no bribe to the temple precinct. All she had was little enough, and she would not have it rejected in scorn. She walked by the gatekeeper with her usual proud arrogance; he almost let her get by. Then suddenly he bawled, “Here, here, mistress, just where do you think you’re going?”

She turned a lofty blind stare in his direction. “I have information for one of the priests or priestesses concerning an old enemy of theirs.”

Her ragged gown and proud bearing was nothing new in any marketplace since the wars, and his mouth twisted slightly in scorn. “I am their ear, madam, and what you would tell them, you may tell me.”

A slight, amused murmur in the crowd of waiting petitioners told her what she had already suspected, that his price for conveying anything at all to his superiors would be far beyond what she could pay. On the other hand, she lost nothing but some time in telling her tale, as long as she did not believe him. Speaking as if she did, she began.

A burst of raucous laughter interrupted her story. “Your bird saw him, mistress? No doubt it can be induced to talk!” The gatekeeper laughed at his own wit. “Shall we take this bird’s oath, and ask what he does at Ithkar Fair?”

Corielle flushed hot. “He is my eyes, and I see through him.”

“Aha!” the gatekeeper exclaimed. “Wizardry! It could be that my masters would wish to speak to you after all, sorceress.” He held out his hand suggestively.

“I have nothing to give you to save myself from a charge of sorcery,” she snapped, her voice ringing clear. “I keep a trained bird like any falconer, and if you would imprison me, you must not only feed me, but my bird. Or would you roast him for your dinner table in lieu of a bribe?”

People did not talk that way to the gatekeeper of the Shrine of the Three Lordly Ones, but to judge from the murmur in the crowd, most fairgoers were glad somebody had!

An open window high in the wall of the shrine now fell shut with a crash of wooden shutters. Soft footsteps pattered down a stairway, and the crowd parted. Skirts rustled, and through the bird’s eyes, Corielle saw an underpriest of the temple, a weedy youth with deference in his very walk. Well trained, she thought, as if he were one of Mother Kallille’s cagebirds.

“You are Corielle, once of Ingnoir?” his voice came softly. She felt something pass before her face and snorted a little in disgust.

“I am,” she said.

“And you say you have seen this Lamok. My master, Ynet, son of Komal, would have me hear your tale, to judge it for himself. He is ... sworn to stay apart,” the youth said nervously, “so I do this for him.”

Like master, like man, Corielle thought, wondering why her heart did not leap at the thought of a priest hearing her tale so soon. But he questioned her in such detail that she knew at last somebody was taking her story seriously. Over and over again, the boy tried to ascertain just how much she had seen, or known at first hand. At last she sighed. “I know it is a very thin tale, Ynet’s apprentice, but there it is.”

Ynet’s apprentice whistled thinly through his teeth. “You have no man and live alone,” he said.

“Fear not,” Corielle said boldly. “I have friends on the fairground, and a kinswoman”—the gods forfend he ever learn she was only eight years old!—“and a foster mother, and my stall neighbors know my name. I need no bodyguard. But it was good of you to think of that.”

The boy’s breath whistled through his teeth again. “You shall hear from my master soon,” he said at last. “Meanwhile, just go about your business as if nothing were amiss, and my master shall see about . . . correcting your distress.”

Then Corielle’s heart did leap, and she reached for his hand. Not finding it, she shrugged in irritation. “Then thank you, lad,” she said, “and thank your master, too, with all my heart.” Pawky flying before her, she went back to her stall in triumph.

Three days went by with no word, and Corielle kept to her stall, anxiously awaiting anything concerning Lamok, or any occurrences that might involve wizardry. Niall said nothing had come to the attention of the fair-wards but added, “If it’s priestly business, we’d not know in any event.” With that she had to be satisfied.

Then, on the morning of the fourth day, when Corielle was returning from a brief visit to the fairground’s edge, Daramil the baker rushed up to her. “Look what came to you by way of a temple serving-lad!” she cried, pressing two sheets of parchment and a small heavy bag into the jeweler’s hand. The bag felt and sounded as if it contained coins. “I swear, he was just waiting for you to be out of the way before he came,” the baker exclaimed.

Corielle felt the bag wonderingly and touched the parchment. “My daughter has a little learning,” Daramil went on eagerly. “Shall I have her read it to you?”

Corielle smiled a little at that, certain that the baker’s daughter had read it already, to everyone in sight! “Please do,” she said.

“To the woman at the jeweler’s stand,” the letter began.

It grieves me to see a decent woman brought so low, so I have commissioned from you a work described on another page, to be finished at your discretion. Your payment will be twenty temple coins, from which you may buy whatever material you please. What is left, taken together with the value of the tools you use, should leave you a respectable dot. I have sent an advance so you can buy yourself a pretty dress and find yourself a man. May your quest be successful.

Ynet, son of Komal.

Corielle frowned as she puzzled over the wording of the letter. But its import was clear: he was financing her search, even to hiring a bravo to aid and protect her. As the realization sank in, joy spread over her face. She shouted, and leaped high in the air, and laughed. Then she thought to ask, “What is this work like that he has asked me to do?”

The baker’s daughter rustled the parchment, then whistled. “It is like lacework, but in metal,” she said in awe. “A pendant, two bracelets, and a pair of ear-bobs, all very delicate, and even the ear-wires are of the finest.”

“Metal

lacework is only another technique,” Corielle said joyously, still singing at the thought of having an ally. “I can use a silver-gold alloy; I will have to buy molds and wax.”

“Your patron spoke of a gown,” the baker reproved her. “He seemed to consider it to be of first importance.”

Corielle sobered. Well, true enough, she looked like a beggar, and people valued her work at the worth of her gown and not her talent. She whistled for Pawky and sent him again to the bird-tent with the message, “Rumara, be my eyes.” As he left, she said with a smile, “Strange, how the gods have given him the gift of speech, but not the wit to say anything of any worth.”

“I know some priests of Thotharn in the same case,” the baker answered with a sniff.

As time went by and neither Rumara nor Pawky came, Corielle remembered that her niece had a hawk in hand to train and, unable to wait any longer, found her way with the aid of a stick to the tent of Ryeth the tailor. “I have a commission and a patron,” she said, singing with the news, “and need a gown. An artisan’s gown in the old style, utterly simple, for my work is to be its only ornament. Rare is the tailor who can make one, since the wars; can you?”

“And be delighted not to have to pay seamstresses to make and tack on all those frills and furbelows the conquerors’ wives loved so,” Ryeth said, a queer catch in her voice. “Besides, you call me tailor, not sewing-woman, so a tailor’s work you shall have of me. Dark red goes with your coloring, but green with your bronzework; what do you say to a mix of colors?”

They were deep in measurements and fitting when a shrill, heartbroken cry of “Aunt!” split the air, and Rumara thrust her way into the tent, sobbing. “Oh, Aunt, where have you been? I have been looking all over for you,” she accused, and laid a small feathered body, soft and still, in Corielle’s hand. “Someone’s murdered Pawky!” the child cried, and wept until the tailor handed her something on which to blow her nose.

“A cruel blow to strike,” Corielle whispered, stunned, as she felt the arrow protruding from the little bird’s back. “Very well.” She got down from the tailor’s stool. “We go hire that bravo now, with no more delay. Rumara, tell Niall the fair-ward. A bird’s life may be nothing to the great ones, but violence is forbidden in this precinct.” Vengeance sang in her voice. “You go lay the accusation before Niall; I will be at the warrior’s wineshop.”

It was not that easy, of course. Rumara had to know what she was doing ordering a gown, and how she had gotten the money. She must read the letter, for Corielle had seen to it she learned her letters. She must sniff at the design; “overfancy,” and ask, “What’s a dot?”

Corielle felt herself blush. “It is a gift of money to a man to be your man. My patron is telling me there should be enough left over for me to—’’

“To get your bed warmed,” the child said impatiently. Well, she had been reared on the fairground, and before that among drudges. Besides, she was right. Corielle, blind and impoverished, was still a woman with a woman’s needs.

“Or a good meal in a wineshop,” she said indifferently, knowing she did not fool Rumara but impelled to show some pride.

She stroked Pawky’s feathered corpse again. “Poor little bird,” she said with tears in her eyes. “Now how sorry I am I so often called you ’birdbrain.’ ”

It was not often that a woman came into the tent where the men who lived by the sword were drinking. Many looked up and choked; some of their rough speech died in midword. Those closest to the entrance, seeing she was blind, called out to her that she was in the wrong place. Others in back whispered and laughed, only because a woman was among them. The owner, a one-eyed veteran, hastened over. “How may the swordsmen of this place serve you, mistress, or do you seek elsewhere?”

“I need a swordsman,” she said, uncertain how to go about this business. “To seek out an old enemy, see if my sister is held captive by him, and avenge the murder of a harmless bird, through whose eyes I last saw him.”

A bold voice called out, “What do you offer in payment, mistress? We are poor men, with our own livings to earn.”

“Name your fees,” she said impatiently, “and I will tell you if I can meet them.”

She barely remembered anything of the rest of the day but the noise and confusion, the clamoring voices, the smell of wine and man-sweat, and the nagging wish that she could read their faces. Some she dismissed readily as too expensive, or stupid, or cruel-seeming, or whining, or half-mad. Many could not be told from any other. The old bartender kept order; she thought she heard Niall the fair-ward in the back of the tent enforcing it, for which she blessed him.

Then, as if in counterpoint to her thoughts, came a soft and tired voice with the accent of the border holdings along Galzar Pass. Just so had Lord Rumagh, border-born, spoken. “You are the jeweler with the bird,” he said gently. “Murdered as an eyewitness to villainy, as so many are?”

“Just so,” Corielle said, swallowing hard. “May I know your name, swordsman?”

“Rumal,” he said in the local speech, the single name marking him as without house or clan. “And if you need a strong and handsome youth, I would not deceive you. But forty years on the battlefield have taught me something, I like to think, and old warriors come cheap. Mistress, I am in sore need of your commission, and besides, your bird’s death angers me.”

He could be telling her what she wanted to hear, to earn a few coins from her; somehow she didn’t care. “How did you come to this, Rumal?” she asked instead.

He laughed a little bitterly. “Shall I tell you I was once lord of a great house? Or that I have had the chance, and would not, for my honor’s sake? Na, what chances I had I threw away, for one reason or another. Tell me of this enemy, and of your sister’s plight.”

Some of the bravos started to drift back to their pursuits as they decided the strange, ragged woman had chosen her man. A few whispered that they made a good pair, for age and his enemies’ blades had marked Rumal deeply. Corielle talked on, oblivious to all of this. At one point the mercenary started. “Lirielle,” he whispered. “I once knew a Lirielle. We were lovers. Go on with your tale, mistress.”

Without realizing it, Corielle found herself telling the mercenary all that had happened in the house of Ingnoir since the conquest and after. “And when our soldiers came through,” she concluded, “I took Rumara and fled, leaving Dunca the horse-master dead with a house warrior’s dagger in him, and made my way here. I tried to learn what had happened to Lirielle, but never found anyone who knew her, or had ever heard of her. I sang her spirit down to death, wept, and took her child to be my own, as I dared not before.”

She could smell cooking and found herself suddenly hungry. “I have forgotten,” she said. “It must be mealtime. Let me buy you whatever you please, and I will have the same.”

The meal, when it came, was soldier’s fare, a stew of beans and strong-flavored vegetables and roots, with tidbits of odd meats, all served with a heaping plate of coarse, flat cakes. She ate with a hearty appetite and puzzled over his concern for strange housefolk in those years. “I dared not,” she answered a question, “because I did not trust Dunca around anything weaker than I was, least of all a maidenchild. He cultivated brutality as other men sharpen their swords.”

She heard a snort from across the table. “I know the breed too well,” he said in disgust, shoving plate and mug away. “It is nearly dark, my lady. May I escort you to your place of business?”

“I had not realized,” she admitted, and rose. He gave her his arm so that she did not need sight to find it.

“Mother Kallille and Rumara would be in bed. Corielle went straight to her stand and stood irresolute. “I sleep under the stand, and it is the only shelter I can offer,” she said. “Nor would I have you misunderstand; I am not the sort of employer to ask you to earn your pay in bed; it is shelter. Unless you desire,” she added painfully, because she suddenly found that she did.

The mercenary stood close by her. “Not

for a crust of bread or a warm place to sleep,” he agreed. “I talked of fee before my fellows, not to seem cheap, but I came with you knowing—”

“Do not be fooled by an old gown,” Corielle said tartly.

The soldier laughed. “But my lady, you ate that meal without complaint, and asked for more. Exquisite courtesy, by the gods!” His voice grew gentle. “But I do like you well, and think it has been overlong since either of us felt the touch of a lover’s hand; to do this would be my pleasure.”

“And mine, too,” she said, and shook her head. “We must both be moon-mad.”

The midnight stars were high in the sky when Corielle moved her hand from the soldier’s face and said sleepily, “My lord.”

Amusement in his voice, he whispered softly, “You are my employer; it is for me to call you my lady.”

Just as softly she answered, “I will keep your secret, and never ask how you came to fail so low, but you should not have let me touch your face and hear your voice together. You are Rumagh, once Lord of Ingnoir. Tell me, does the Lady Mareth live?”

“She lives and is well. I will also tell you this,” he said with honest regret. “I am still her sworn man, and can give nobody more than the crumbs from her table, Corielle. But what I do give will be honestly given.”

She touched his hand in reassurance. “But how did you come to a mercenary’s hiring hall?” she asked then.

Rumagh of Ingnoir stretched and collected his thoughts. “My lady thought the evils which had befallen us since we took back our land could not be explained by natural means. Too many crops failed among our friends; too many women and she-animals miscarried, as did Mareth herself. The old healer wandered in her mind; age, they called it, but I am no younger. Those so attacked were all the conqueror’s enemies and our friends, and the priestesses called it wizardry. So I am here to seek a wizard.” He laughed a little. “One bright spot in all this blight; the cheesemaker was delivered of a fine, fat daughter, also named Rumara.”

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

Space Service Perilous Dreams

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

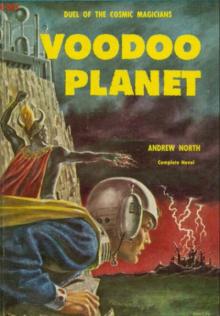

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1