- Home

- Andre Norton

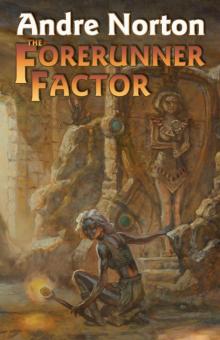

The Forerunner Factor Page 14

The Forerunner Factor Read online

Page 14

“This is only a small, a very small example of such weapons.” He did not explain, she noted, how he had come by what he held; she was very sure he could not have brought it with him through the desert. The thing was too large to have been concealed anywhere among their belongings.

“No,” he was continuing, “there were other fire throwers, such as could consume all of Kuxortal within a flash of thought. Much of my world died so. There were left only small pockets which held life. And the few of my own species who survived—they changed—or their children did. Some died because the changes were such as they became monsters who could not live. A few, so very few, were still human in form. Only they were now born armored against the force of weapons such as those that had killed their world—unless the fire touched them directly.

“For it is also the curse of such a war that the very air was poisoned. Those who breathed it, ventured into certain places, died, not quickly as in the fire, but slowly and with great pain and suffering. Back there—that pool . . .”

“It kills?” she asked slowly. But she had felt no pain. Perhaps that was yet to come. She refused to allow herself to think that she might be akin to those withered, sun-baked things by the shore. Or, worse still, come to be what she had seen in the shell of metal.

“No, I think not.” He looked honestly puzzled. “Tell me, how did you feel when you were out of the water—or whatever that liquid may be?”

“Good. And look at Zass.” Simsa made up her mind she would not believe that she had been floating in something which would leave her dead. “She can unfold her bad wing; almost, she can fly again.”

“Yes. It renews. Only there is something also near here which is the opposite; it kills!”

Now he did begin to move closer to her, but this time Simsa did not shrink away. He was holding out that strip of metal he had worn, in open invitation for her to look at it.

“When I came out of the pool—after I had drawn you in, since you were not conscious, nor able to help yourself—I found this thing you see. So, I pulled you part-way out and came to explore because of what can be read here.”

Thorn placed his rod weapon on the pavement, pointed now with his free hand to the strip. There was a distinct line of red upward along it.

“This showed me danger—the very danger which my kind know well from their own past. It might have meant that before us was death—perhaps not for me, but for you and your creatures. I had to find the source, know whether or not there was a deadly radiation.”

“You took the carrier,” Simsa pointed out.

Again he nodded. “If there was the degree of radiation which this indicated, then the food, the water on it might already be poisoned for you. I had to make sure that you did not eat or drink before you left the pool chamber and I was not there to warn.”

“And is what we brought poisoned?” She wondered if he knew that this tale was a weak one. She would have laughed had this been told to her by another, yet she could not judge the off-worlder by the measure of the men in Kuxortal. He was different—and perhaps she was a four-time fool to ever put any trust in him.

“No. The source of the trouble lies there—” He half turned, to point backwards at the Guardian, or perhaps to the passage beyond that motionless figure, from which he had come.

“And where did you get that?” It was Simsa’s turn to point—this time to the weapon he had laid down.

“Where I came out into the open. It was just lying there . . .”

“But not of this city,” she prodded when he hesitated. “How did a weapon from the stars—and those—” she indicated the guardian, “arrive here? Did they come then with your brother? Or were they on that ship which you said landed secretly? I thought that it was the rule that you did not bring such weapons to a world where they were not known. These who have waited so long, do they not wear the garments which are also of starships? I have heard of such—which allow one to walk on those worlds where one cannot breathe the air or live without protection. Who came thus?”

“These have nothing to do with T’seng. They have been here far longer and our people knew nothing of them. There is a small flyer, not one from the stars, but one such we use to explore new worlds. It rests beyond,” he nodded again to the passage, “where it crashed. There was fighting here—a long time ago. Perhaps between outlaws and the Patrol.” He stooped to pick up the weapon once again. “There is only a half-charge in this, less now since I tried it. Also, this weapon is of a type which is very old and not in use any longer.”

He had an answer for everything, Simsa thought, which did not make her feel any easier. That wonderful sensation of well-being which had been hers when she had come forth from the pool, that was still a part of her body perhaps, but it no longer soothed and filled her mind. She was retreating fast into the mold of the Burrowers where trust was too high a price for anyone to pay.

“Was this really,” she was guessing now but the thought which had come to her suddenly seemed to make sense, “what your brother sought here?”

“Of course not!” Impatience lent a snap into his answer. “But . . .” His oddly shaped eyes changed in a fashion to give him a speculative look, somewhat eager. She could almost see Zass in him now—a Zass who had sensed a ver-rat near to hand. “But perhaps this would explain better why my brother did not return!”

“He was slain by dead men?”

“This!” He seemed not to have heard her retort, instead he held that off-world weapon out at full arm’s length, surveyed it as if he had indeed unearthed some treasure which would give him the wealth of a river captain after a full season’s fortunate trading. “Tell me, Simsa, what would one of your Guild Lords offer for such weapons, weapons which can kill at a distance, putting their bearers in no danger, but blasting the enemy entirely?”

“You spoke of fire, of cities being eaten up by it,” she pointed out. “What good would it do to destroy all that which could be traded for? No lord would send out his guards if he got no loot in return—not even one of the northern pirates would be so foolish. And they will risk more than any trader. The Lords live for trade, not the destruction of it.”

“Only, such as this would not level a city. Its range is very limited. At its widest setting it could not destroy more than would be on this carrier.”

Simsa looked from the slender rod to the carrier. She had seen the destruction on the upper wall, but what did any Burrower really know of the feuds of the Guild Lords or the thieves’ leaders? Men died in formal duels, in feuds. There had always been raiding of the river convoys, pirates in the northern seas.

Weapons such as this would make a raid harmless for those who used them and they could take, say, the fleet from Saux, the richest prize ever to set anchor in Kuxortal. It would be as a flock of zorsals lighting upon a pack of ver-rats caught in the open with no holes ready gnawed for their escape.

“You begin to understand? Yes, given ambition, greed, the need for power over others—”

“You think of Lord Arfellen!” She made that a statement not a question. “Men have started talking of him behind their hands. The river trader—Yu-i-pul—last season he brought down such a cargo of weft-silk as most of the city marveled. He would not put it to auction after the custom, but held it, held it in Gathar’s warehouse.” (The significance of that—maybe it meant something). “Yes—Basher’s story—Basher’s story!”

It was like puzzling out one of the ancient pieces of carving and coming suddenly on a bit which, when fitted into its rightful place, gave meaning to the whole of the find.

“What was Basher’s story?”

Simsa wrinkled her nose. “He is a great zut and would have men afraid of him—always he speaks much of what he knows—so that few listen to him and know that there is ever a grain of truth in his yammering. But he would have it that one of Yu-i-pul’s guard got sick-drunk on that rot-wine in the Shorehawl and said that there was trouble, that Yu-i-pul knew an auction would not be profitable

because of some meddling and, therefore, he would wait out the coming of the ship traders himself. Which he did, though all the city knew that Lord Arfellen was in a rage. It is said that he killed the one who brought him some news of the matter. But the cargo was in Gathar’s warehouse in spite of the Guild Lords and Yu-i-pul took home more in trade than any river man has ever hauled upstream. There were five barges and his men were armed with good swords and spears which he had forged for them under his captains’ own inspection.

“That was a season ago. Only—what Yu-i-pul has done, so can another river man try. If it goes so, and the auctions are used less and less, then the Guild Lords will feel the pinch.”

Matters which had meant nothing to a Burrower, nothing to her save that it had been the initial coming of the very perishable cargo into Gathar’s care which had led him to make the bargain with her for the zorsal use (there was a taste or smell to weft-silk which drew ver-rats as sweet gum could draw the Burrow insects).

“Have cargoes coming down the river ever been plundered?”

“It has been tried many times. Sometimes, such did change hands and those bringing the barges into Kuxortal have washed their blades of trader blood well up stream. But the traders of the river road are no weaklings. Such as Yu-i-pul have men sworn to him and his family, father to son. They have stakes in the selling and it is partly their own gain which they would fight for. Yu-i-pul has battled off several attacks in past seasons. They know enough of him and his men now to let his Red and Gold Serpent pennant pass through any of the narrows without challenge. That was why he could say no auction. The Guild wanted no fighting along the wharves, for threaten one river trader in the city and all will answer his warn-war horn, even if they would thrust him through the next day in some feud of their own kind.”

“So,” the off-worlder dropped down on the pavement, his weapon resting across his knees. He was no longer looking at her but rather at the greenery beyond her shoulder.

Though upper city feuds meant nothing, the more Simsa had talked, the more her own thoughts had leaped from one known fact to a new surmise. As he had done, she relaxed, seated herself, giving the carrier a light shove so that it bobbed a little away, no longer any barrier between them.

“You think that if Lord Arfellen knew that such as those,” she pointed to the rod, “were to be found here, he would send men to seek them out, arm his guard, and venture up river to wait for Yu-i-pul? I think so, too. He is not a man to take lightly to insults and Yu-i-pul made him look small in the eyes of those who knew him best—if Baslter’s story was the truth. Also, he would be afraid that your brother might discover what lay here. But would he not already have taken these weapons and had them hidden?”

“He could not hide what lies there. Any off-worlder chancing upon it would be required to report it to the Patrol. They would send in their own team, to clean up, to make sure that just that did not happen, that nothing of off-world weaponry would be available to such as Lord Arfellen. I do not know why the first ship landing in these hills did not pick up the radiation reports. Or if they did,” he hesitated, “more may be behind this than I first believed.”

There had come a change into his face which never seemed open to Simsa’s eyes. Now there was a tightness about his lips, once more those lids drooped so she could not see what fire might lie in his eyes. There was something harder, stronger, closed and yet sharper about him, as if some emotion within had given him a new and keener purpose.

“You believe your brother is dead?” she asked quietly.

Still he did not look at her. “Of that I am going to make sure.”

That was no oath sworn by blood drip or brother drink, still his words would hold him, of that she was certain. Watching him now, she knew that she would not want to be one to whom he threw a feud challenge.

“You think that they have been here—and Lord Arfellen might have sent them. But how would they know anything about it?” Simsa was suddenly struck by that. If a crashed starship, or even part of such a one, had been found, that story could never have been suppressed in Kuxortal. There was too much interest always in the spacers and all which pertained to them.

“They might not have known about this—at first. But there have long been stories of treasures hidden in the Hard Hills. So when my brother, an off-worlder, came to hunt for such, might they not have believed that he was in search of something more than the source of very old things?”

Simsa’s Burrower shrewdness accepted that. Naturally, an off-worlder who came to search the Hard Hills would be assumed by Guild men to be hunting more than broken bits of stone, no matter what might be lettered on such. Though she herself had a lanquid interest in that direction because of Ferwar’s addiction and the fact that there was a market among starmen for pieces, she would never have thought that anyone would cross space and then the desert land in quest of those alone, unless he was a victim of some madness.

There was the ring on her hand. She made a fist now by curling her fingers together so that the tower with the gem roof stood stolid and tall. There were those other pieces—the necklace which still rested its pale stones, like the tears shed by a weeping tree, between her breasts, the cuff—

She felt now within her sleeve pocket and brought that out. In the sun here it came to life, not brilliantly, but with a steady glow. At the same time, she jerked open the coat to show the gems resting against her dark skin.

“There may be treasure here also.” Deliberately, she tossed the cuff through the air and saw him, in swift reflective action, catch it.

“These were the best of Ferwar’s things. I do not believe that they came originally from Kuxortal. There is nothing about them which is of the city. Nor are the stones as are set here,” she picked up the long, narrow strip which formed the pendant and held that into the sun in turn, “any such as I have seen brought overseas or down river.

“The Old One had dealings with faceless ones who made sure that they were not seen coming or going. I do not know from where these came. But it is true that seasons ago there was some small trade with the desert men. Then those came no more and instead there was a story of a plague which killed quickly—”

Though he turned the cuff about in his hands, his attention was no longer for that. Instead, he leaned forward, staring at her, his eyes wide open as they seldom were, eagerness visible in every line of his taut body.

“A plague which killed quickly!” he repeated. “Of what nature?”

Again, her thoughts took one of those sudden leaps. It was as if her whole mind could half sense what lay in his from time to time. She dropped the pendant back against her breast, waved her ringless hand towards that grim guardian which she could see the best.

“What you said of the air which could carry some poison in it where your weapons had been used—a plague!”

“Yes!” he was on his feet again in one fluid movement. Then turned to demand of her:

“This plague—how long ago?”

The Burrowers did not reckon time, they had no reason to. One season followed another. One said that this or that happened in the year the river rose and Hamel and his woman were drowned, or in the season that the Thieves took Roso to be a climbing man—that was the way the Burrowers remembered. If the Guilds numbered their years, Simsa had no way of telling by their time. But she tried to think back to the last time that bone-lean man who had brought Ferwar the most and best of her private gleanings had come to them.

He was a river trader of the smallest fringe of that order, one who could never reckon more profit than might feed him and his crew of two boys, as hungry and meager as himself, for more than a voyage—-if they were that lucky. She began to count on her fingers.

“Twelve seasons ago—Thrag came. He had found a desert man by the river, dying. He waited for his death and then took what he had. But,” she frowned, “the Old One said it was cursed. She paid him, but said to bring no more and she wrapped it many times over and had me bury it under s

tones. It was a jar of some kind. I remember she asked Thrag what the desert man died of, and then she was angry and told him that it was a devil and had doubtless touched him also. He ran. Nor—it is true—did he ever come again.”

One did not question the Old One, Simsa had learned that as the first and foremost rule of her life, so early she could not remember when she did not know it. Now thinking on what had happened: Thrag, the dead man from the desert, the fact that men had commented that the desert people in the following seasons had disappeared, all came together in another of those quick forming patterns.

“Twelve seasons ago, six of your years,” Thorn was speaking his thoughts aloud again. “These desert people could have stumbled on a radioactive wreck, plundered it . . .”

“The plague being that kind which slaughtered your people in the long ago? But there was no war here.”

“No war for your people that is true. But two enemies, two ships, one hunting the other, so driven by fear or need for revenge as to loose the last weapon—a crash; it fits! By the Sages of the Ninth Circle, it fits!”

“But you said that what you found was not a ship out of space,” she reminded him.

“No. But it could have come from such a ship, used for escape by survivors who were still hunted men.”

“And who now stand there—and there!” Deliberately, she pointed first to one of those guardians and then to the other. “But why do they stand so? I thought them guards. If they had died of plague or fought and killed each other, then why do they still stand so, one at either end of this way? That is the fashion in which guards of the Guild stand before a door which none but a high one can enter.”

Thorn turned his head slowly, surveying first one and then the other of the motionless, suited bodies.

“You are right,” he said thoughtfully. “There is something very purposeful in the way they were left, perhaps as guards—perhaps for some other reason.”

“Were they—” Remembering what she had seen within the bubble-like helmet, she gave a small gulp, and then continued with what easiness she could summon, “Were these of your people? Or could you tell?”

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

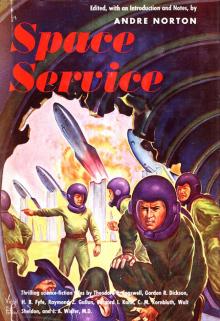

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

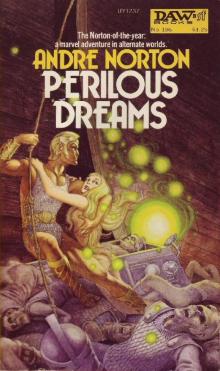

Space Service Perilous Dreams

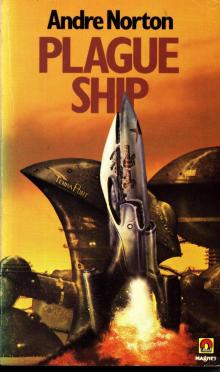

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

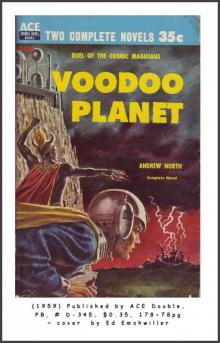

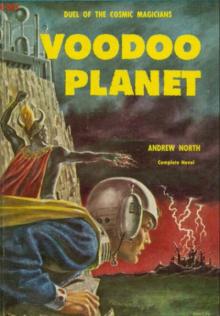

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

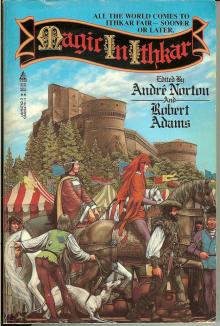

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1