- Home

- Andre Norton

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Page 2

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Read online

Page 2

“Ho, Lura!”

The cat paused at his exultant call and swung the dark brown mask of her face toward him. Then she meowed plaintively, conveying the thought that she was being greatly misused by this excursion into the dampness of an exceedingly unpleasant day.

She was beautiful indeed. Fors’ feeling of good will and happiness grew within him as he watched her. Since he had left the last step of the mountain trail he had felt a curious sense of freedom and for the first time in his life he did not care about the color of his hair or feel that he must be inferior to die others of the clan. He had all his father had taught him well in mind, and in the pouch swinging at his side his father’s greatest secret. He had a long bow no other youth of his age could string, a bow of his own making. His sword was sharp and balanced to suit his hand alone. There was all the lower world before him and the best of companions to match his steps.

Lura licked at her wet fur and Fors caught a flash of— was it her thoughts or just emotion? None of the Eyrie dwellers had ever ben able to decide how the great cats wer able to communicate with the men they chose to honor with their company. Once there had been dogs to run with man—Fors had read of them. But the strange radiation sickness had been fatal to the dogs of the Eyrie and their breed had died out forever.

Because of.that same plague the cats had changed. Small domestic animals of untamable independence had produced larger offspring with even quicker minds and greater strength. Mating with wild felines from the tainted plains had established the new mutation. The creature which now rubbed against Fors was the size of a mountain lion of pre-Blow-up days, but her thick fur was of a deep shade of cream, darkening on head, legs, and tail to a chocolate brown—after the coloring set by a Siamese ancestor first brought into the mountains by the wife of a research engineer. Her eyes were the deep sapphire blue of a true gem, but her claws were cruelly sharp and she was a. master hunter.

That taste possessed her now as she drew Fors’ attention to a patch of moist ground where the slot of a deer was deep marked. The trail was fresh—even as he studied it a bit of sand tumbled from the top into die hollow of the mark. Deer meat was good and he had few supplies. It might be worth turning aside. He need not speak to Lura—she knew his decision and was off on the trail at once. He padded after her with the noiseless woods walk he had learned so long before that he could not remember the lessons.

The trail led off at a right angle from the remains of the old road, across the tumbled line of a wall where old bricks protruded at crazy points from heaped earth and brush. Water from leaves and branches doused both hunters, gluing Fors’ homespun leggings to his legs and squeezing into his boots.

He was puzzled. By the signs, the deer had been fleeing for its life and yet whatever menaced it had left no trace. But Fors was not afraid. He had never met any living thing, man or animal, which could stand against the force of his steeltipped arrows or which he would have hesitated to face, short sword in hand.

Between the men of the mountains and the roving Plainsmen there was a truce. The Star Men often lived for periods of time in the skin-walled tents of the herders, exchanging knowledge of far places with those eternal wanderers. And his father had taken a wife among tine outlanders. Of course, there was war to the death between the humankind and the Beast Things which skulked in the city ruins. But the latter had never been known to venture far from their dank, evil-smelling burrows in the shattered buildings, and certainly one need not fear meeting with them in this sort of open country! So he followed the trail with a certain reckless disregard.

The trail ended suddenly on the tip of a small gully. Some ten feet or so below, a stream—swollen by the rain —frothed around green-grown rocks. Lura was on her belly, pulling her body forward along the rim of the ravine. Fors dropped down and inched behind a bush. He knew better than to interfere with her skilled approach.

When the tip of her brown tail quivered he watched for a trembling of Lura’s flanks which would signalize her spring. But instead the tail suddenly bristled and the shoulders hunched as if to put a brake upon muscles already tensed. He caught her message of bewilderment, of disgust and, yes, of fear.

He knew that he had better eyesight than almost all of the Eyrie men, that had been proved many times. But what had stopped Lura in her tracks was gone. True, upstream a bush still swayed as if something had just pushed past it. But the sound of the water covered any noise and although he strained—there was nothing to see.

Lura’s ears lay flat against her skull and her eyes were slits of blazing rage. But beneath the rage Fors grasped another emotion—almost fear. The big cat had come across something strange and therefore to be considered with suspicion. Aroused by her message Fors lowered himself over the edge of the gully. Lura made no attempt to stop him. Whatever had troubled her was gone, but he was determined to see what traces it might have left in its passing.

The greenish stones of the river bank were sleek and slippery with spray, and twice he had to catch hurriedly at bushes to keep from falling into the stream. He got to his hands and knees to move across one rock and then he was at the edge of the bush which had fluttered.

A red pool, sticky but already being diluted by the rain and the spray, filled a clay hollow. He tasted it with the aid of a finger. Blood. Probably that of the deer they had been following.

Then, just beyond, he saw the spoor of the hunter that had brought it down. It was stamped boldly into the clay, deeply as if the creature that made it had balanced for a moment under a weight, perhaps the body of the deer. And it was too clear to mistake the outline—the print of a naked foot.

No man of the Eyrie, no Plainsman had left that trackl It was narrow and the same width from heel to toe—as if the thing which had left it was completely flat-footed. The toes were much too long and skeleton-thin. Beyond their tips were indentations of—not nails—but what must be real claws!

Fors’ skin crawled. Its was unhealthy—that was the word which came into his mind as he stared at the track. He was glad—and then ashamed of that same gladness— that he had not seen the hunter in person.

Lura pushed past him. She tasted the blood with a dainty tongue and then lapped it once or twice before she came on to inspect his find. Again flattened ears and wrinkled, snarling lips gave voice to her opinion of the vanished hunter. Fors strung his bow for action. For the first time the chill of the day struck him. He shivered as a flood of water spouted at him over the rocks.

With more caution they went back up the slope. Lura showed no inclination to follow any trail the unknown hunter might have left and Fors did not suggest it to her. This wild world was Lura’s real home and more than once the life of a Star Man had “depended upon the instincts of his hunting cat. If Lura saw no reason to risk her skin downriver, he would abide by her choice.

They came back to the road. But now Fors used hunting craft and the trail-covering tricks which normally one kept only for the environs of a ruined city—those haunted places where death still lay in wait to strike down the unwary. It had stopped raining but the clouds did not lift.

Toward noon he brought down a fat bird Lura flushed out of a tangle of brush and they shared the raw flesh of the fowl equally.

It was close to dusk, a shadow time coming early because of the storm, when they came out upon a hill above the dead village the old road served.

2. INTO THE MIDST OF YESTERDAY

Even in the pre-Blow-up days when it had been lived in, the town must have been neither large nor impressive. But to Fors, who had never before seen any buildings but those of the Eyrie, it was utterly strange and even a bit frightening. The wild vegetation had made its claim and moldering houses were now only lumps tinder the greenery. One water-worn pier at the edge of the river which divided the town marked a bridge long since fallen away.

Fors hesitated on the heights above for several long minutes. There was a forbidding quality in that tangled wilderness below, a sort of moldy rankness rising on the

evening wind from the hollow which cupped the ruins. Wind, storm and wild animals had had their way there too long.

On the road to one side was a heap of rusted metal which he thought must be the remains of a car such as the men of the old days had used for transportation. Even then it must have been an old one. Because just before the Blow-up they had perfected another type, powered by atom engines. Sometimes Star Men had found those almost intact. He skirted the wreckage and, keeping to the thread of battered road, went down into the town.

Lura trotted beside him, her head high as she tested each passing breeze for scent. Quail took flight into the tall grass and somewhere a cock pheasant called. Twice the scut of a rabbit showed white and clear against the green.

There were flowers in that tangle, defending themselves with hooked thorns, the running vines which bore them looped and relooped into barriers he could not crash through. And all at once the setting sun broke between cloud lines to bring their scarlet petals into angry life. Insects chirped in the grass. The storm was over.

The travelers pushed through into an open space bordered on all sides by crumbling mounds of buildings. From somewhere came the sound of water and Fors beat a bath through the rank shrubbery to where a trickle of a stream fed a manmade basin.

In the lowlands water must always be suspect—he knew that. But the clear stream before him was much more appetizing than the musty stuff which had sloshed all day in the canteen at his belt. Lura lapped it unafraid, shaking her head to free her whiskers from stray drops. So he dared to cup up a palmful and sip it gingerly.

The pool lay directly before a freak formation of rocks which might have once been heaped up to suggest a cave. And the mat of leaves which had collected inside there was dry. He crept in. Surely there would be no danger in camping here. One never slept in any of the old houses, of course. There was no way of telling whether the ghosts of ancient disease still lingered in their rottenness. Men had died from that carelessness. But here—In among the leaves he saw white bones. Some other hunter—a four-footed one—had already dined.

Fors kicked out the refuse and went prospecting for wood not too sodden to burn. There were places in and among the clustered rocks where winds had piled branches and he returned to the cave with one, then two, and finally three armloads, which he piled within reaching distance.

Out in the plains fire could be an enemy as well as a friend. A carelessly tended blaze in the wide grasslands might start one of the oceans of flame which would run for miles driving all living things before it. And in an enemy’s country it was instant betrayal. So even when he had his small circle of sticks in place Fors hesitated, flint and steel in hand. There was the mysterious hunter—what if he were lurking now in the maze of the ruined town?

Yet both he and Lura were chilled and soaked by the rain. To sleep cold might mean illness to come. And, while he could stomach raw meat when he had to, he relished it broiled much more. In the end it was the thought of the meat which won over his caution, but even when a thread of flame arose from the center of his wheel of sticks, his hand still hovered ready to put

it out. Then Lura came up to watch the flames and he knew that she would not be so at her ease if any danger threatened. Lura’s eyes and nose were both infinitely better than his own.

Later, simply by freezing into a hunter’s immobility by the pool, he was able to knock over three rabbits. Giving Lur.a two, he skinned and broiled the third. The setting sun was red and by the old signs he could hope for a clear day tomorrow. He licked his fingers, dabbled them in the water, and wiped them on a tuft of grass. Then for the first time that day he opened the pouch he had stolen before the dawn.

He knew what was inside, but this was the first time in years that he held in his hand again the sheaf of brittle old papers and read the words which had been carefully traced across them in his father’s small, even script. Yes —he was humming a broken little tune—it was here, the scrap of map his father had treasured so—the one which showed the city to the north, a city which his father had hoped was safe and yet large enough to yield rich loot for the Eyrie.

But it was not easy to read his father’s cryptic notes. Langdon had made them for his own use and Fors could only guess at the meaning of such directions as “snake river to the west of barrens,” “Northeast of the wide forest” and all the rest. Landmarks on the old maps were now gone, or else so altered by time that a man might pass a turning point and never know it. As Fors frowned over the scrap which had led his father to his death he began to realize a little of the enormity of the task before him. Why, he didn’t even know all the safe trails which had been blazed by the Star Men through the years, except by hearsay. And if he became lost— His fingers tightened around the roll of precious papers. Lost in the lowlands! To wander off the trails—!

Silky fur pressed against him and a round head butted his ribs. Lura had caught that sudden nip of fear and was answering it in her own way. Fors’ lungs filled slowly. The humid air of the lowlands lacked the keen bite of the mountain winds. But he was free and he was a man.

To return to the Eyrie was to acknowledge defeat. What if he did lose himself down here? There was a whole wide land to make his own! Why, he could go on and on across it until he reached the salt sea which tradition said lay at the rim of the world. This whole land was his for the exploring!

He delved deeper into the bag on his knee. Besides the notes and the torn map he found the compass he had hoped would be there, a small wooden case containing pencils, a package of bandages and wound salve, two small surgical knives, and a roughly fashioned notebook —the daily record of a Star Man. But to his vast disappointment the entries there were merely a record of distances. On impulse he set down on one of the blank pages an account of his own day’s travel, trying to make a drawing of the strange footprint. Then he repacked the pouch.

Lura’ stretched out on the leaf bed and he flopped down beside her, pulling the blanket over them both. It was twilight now. He pushed the sticks in toward the center of the fire so that unburnt ends would be consumed. The soft rumble of the cat’s purr as she washed her paws, biting at the spaces between her claws, made his eyes heavy. He flung an arm over her back and she favored him with a lick of her-tongue. The rasp of it across his skin was the last thing he clearly remembered. There were birds in the morning, a whole flock of them, and they did not approve of Lura. Their scolding cries brought Fors awake. He rubbed his eyes and looked out groggily at a gray world. Lura sat in the mouth of the cave, paying no attention to the chorus over her head. She yawned and looked back at Fors with some impatience.

He dragged himself out to join her and pulled off his roughly dried clothes before bathing in the pool. It was cold enough to set him sputtering and Lura withdrew to a safe distance. The birds flew away in a black flock. Fors dressed, lacing up his sleeveless jerkin and fastening his boots and belt with extra care.

A more experienced explorer would not have wasted

time on the forgotten town. Long ago any useful loot it might have once contained had either been taken or had moldered into rubbish. But it was the first dead place Fors had seen and he could not leave it without some examination. He followed the road around the square. Only one building still stood unharmed enough to allow entrance. Its stone walls were rank with ivy and moss and its empty windows blind. He shuffled through the dried leaves and grass which masked the broad flight of steps leading to its wide door.

There was the whir of disturbed grasshoppers in the leaves, a wasp sang past. Lura pawed at something which lay just within the doorway. It rolled away into the dusk of the interior and they followed. Fors stopped to trace with an inquiring finger the letters on a bronze plate. “First National Bank of Glentown.” He read the words aloud and they echoed hollowly down the long room, through the empty cage-like booths along the wall.

“First National Bank,” he repeated. What was a bank? He had only a vague idea—some sort of a storage place. And this dead town must

be Glentown—or once it had been Glentown.

Lura had found again her round toy and was batting it along the cracked flooring. It skidded to strike the base of one of the cages just in front of Fors. Round eyeholes stared up at him accusingly from a half-crushed skull. He stooped and picked it up to set it on the stone shelf. Dust arose in a thick puff. A pile of coins spun and jingled in all directions, their metallic tinkle clear.

There were lots of the coins here, all along the shelves behind the cage fronts. He scooped up handfuls and sent them rolling to amuse Lura. But they had no value. A piece of good, rust-proof steel would be worth the taking—not these. The darkness of the place began to oppress him and no matter which way he turned he thought he could feel the gaze of that empty skull. He left, calling Lura to follow.

There was a dankness in the heart of this town, the air here had the faint corruption of ancient decay, mixed with the fresher scent of rotting wood and moldering vegetation. He wrinkled his nose against it and pushed on down a choked street, climbing over piles of rubble, heading toward the river. That stream had to be crossed some way if he were to travel straight to the goal his father had mapped. It would be easy for him to swim the thick brownish water, still roily from the storm, but he knew that Lura would not willingly venture in and he was certainly not going to leave her behind.

Fors struck out east along the bank above the flood. A raft of some sort would be the answer, but he would have to get away from the ruins before he could find trees. And he chafed at the loss of time.

Th’ere was a sun today, climbing up, striking specks of light from the water. By turning his head he could still see the foothills and, behind them, the blueish heights down which he had come twenty-four hours before. But he glanced back only once, his attention was all for the river now.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

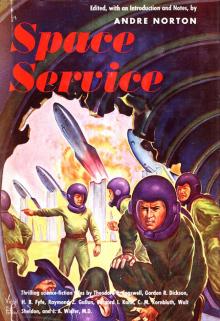

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

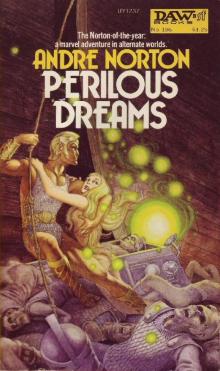

Space Service Perilous Dreams

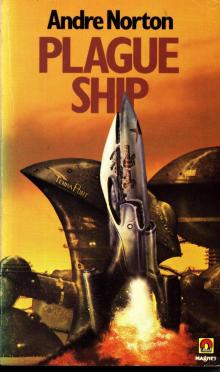

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

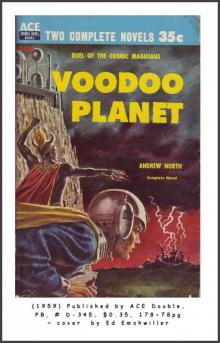

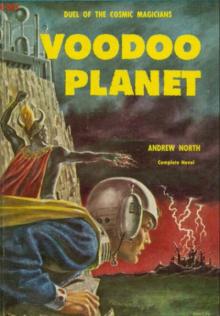

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

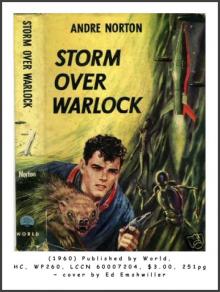

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

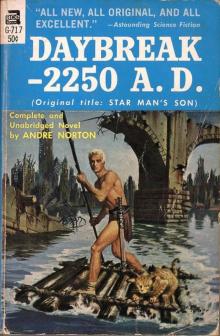

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

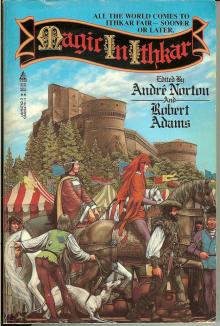

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1