- Home

- Andre Norton

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Page 2

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Read online

Page 2

“This is for you alone and it shall be a key to that which is meant. Do not let it go from you.”

When I protested that such a piece was worth a fortune she shook her head.

“It goes where it will. Now it is yours—I think—” She frowned a little. “No, the fate of another is not for my telling—take it, Hynkkel, and learn.”

I had other luck that day, obtaining a very fine piece of turquoise which I knew would delight Kura, and I returned home, the cat head still on my breast, Mieu croon-purring on the top of my loaded yaksen.

However, I quickly found that I was wrong in believing that Ravinga’s unexpected gift was a mark of good fortune. That I speedily discovered shortly after I reached the rock island which was home for my House. One travels best by night and certainly never under the full punishment of the sun, and so it was dawn when I passed the last of the towering carven sentry cats and saw my brother and Kura both heading towards me as I plodded wearily along.

Kura I expected, for my sister was always impatient to learn how well her wares had sold and what raw materials I had bought to build up her store. However, that Kalikku would pay any attention was certainly new.

As usual he was fighting his mount as he came. To Kalikku any animal must be harshly mastered, and most of his, so ridden, were so vicious that none other of the family chose to go near them. He felt always deprived because the days of war when one family or clan turned against another in open battle had passed, listening eagerly and with close attention to my father’s stories of past engagements. Hunting and forays for caravan raiders were all he might look to, and who would become, he thought, a hero from such petty trials of strength?

I halted, waiting for them to join me, which they did speedily, Kalikku reining in with a swift cruelty which made his oryxen rear, sending sand showering. Mieu sat up and growled, turning a very unfriendly eye upon my brother.

“Foot padder”—that was one of the least cutting of the names my brother could call me, and did—“make haste. Your labors are—” He did not finish; instead he leaned forward and stared, not eye to eye, but rather at the pendant I still wore.

The oryxen snorted and danced sideways as his rider urged the animal closer to me. “Where got you that?” my brother demanded. “How much of our father’s store money did you lay out for it? Kura,” he said to my sister, “perhaps it was your market profit this one has plundered.”

Now he favored me with that ever-present challenge I had seen most of my life, silently urging me to retort either by fist or voice. And, as ever, I refused to give him the pleasure he had once taken, when we were very young, of beating me at will.

“It was a gift.” Beneath my journey cloak my hands clenched and then by the force of my will loosened again.

“A gift!” My brother laughed scornfully. “From whom could such as you receive that! Though I wager you certainly would not have the spirit to take it by any force.”

Kura moved closer also. Seeing the interest in her eyes I slipped the pendant from my head and handed it to her. She turned it round and round, running her fingers over it. “No,” she said musingly, “this is not from the hands of Tupa” (she mentioned one of the greatest artists of our people). “It is too old and also it is—” She hesitated and then added, “Truly finer work than I have ever seen. Whence did it come, brother?”

“From Ravinga, the dollmaker of Vapala, whom I have met several times in the market.”

My sister held it as if she were caressing the fashioning of stones and metal.

“Whence did she get it, then?”

I shrugged. “That I do not know and—”

However, I had no time to finish what I would say, for Kalikku made a snatch for it, one which Kura was fast enough to avoid. “It is a treasure for a warrior, not for one who labors by his will,” he proclaimed loudly, “Rightly such is mine!”

“No.” For the first time I refused to be bullied. During all the night hours of my travel, that had rested not far from my heart. A belief had grown stronger in me with every step that it was indeed now a part of me. I did not really know what it portended nor why I should feel it now so, but I did.

“No?” My brother showed his teeth in a grin like that of a Sand Cat seeing its prey at easy distance from it. “What is this dollmaker then to you that she gives you a treasure and you would hold it—your mat mate?”

“Stop it!” Kura seldom raised her voice. Ofttimes she was so intent upon her thoughts and plans for her work that she hardly seemed to be with us.

She dropped chain and pendant into my hand again. “If Hynkkel says this is a gift, then that is so. And one does not take gifts except for good reason, nor does one then surrender such to another. Hynkkel, I would like to look upon it again and perhaps make a drawing of it for my files, if you are willing.”

“I am always at your service,” I said.

Among us we have no slaves—that is for the barbarians of Azhengir. Our servants are free to come and go as they well please—but usually as a caste they have their own well-earned positions and a different kind of pride. That I should be as a servant in my father’s house was because I was a failure as a son, a son he thought was not worthy of his notice. I was early a failure at those very things a warrior must know or do.

Bodily my strength was never that of my brother and I disliked all that went to make up his life. Though I had buried deep within me the pain—I always knew that my father denied me—I was content in other ways. I worked with our herds, I was careful as a tender of our algae beds, and I was always willing to go to the market. However, to my father’s mind I was no proper one to inherit his name. It is true that I have always been something of a dreamer. I longed to make beauty with my hands as did Kura—but the one awkward figure of a cat guardian I chipped from stone was far from any masterpiece, though I stubbornly set it up beside my door, even as my father and brother had their “battle” standards beside theirs.

So, there being no middle way, I was a servant and that I tried to take pride in—making sure I served well. Thus I used a servant’s response to my sister.

“You are needed.” She drew a little away from me now as if, though she had taken my part, that was only in fairness and now we were back again in the same relationship we had been in for most of my life. “Siggura has come into heat. We must have the feast of choosing. There is much to be done. Already messages to other clans have been sent by the drummers.”

Kalikku laughed. “Do you not envy her, Kura—the feasting, the coming of many wooers?” His tone was meant to cut as might the lash of his riding whip.

She laughed in turn but hers was honest laughter. “No, I do not.” She lifted her hands and held them out, letting fall the reins of her well-trained mount. “It is what these can do which gives my life meaning. There is no envy in me for Siggura.”

Thus I had come back to pressure of hurry. Not all of our women are designed to wed. Some never come into heat. I do not know whether many of them regret that or not. But I did know that Siggura was one who would make the most of this chance to be the center of feasting and attention, which might last for a week or more, until she was ready to announce her mate choice.

So it was that I got scanty sleep that day but hurried to oversee the checking of supplies, the dispatching of the others of our serving people to this or that task. The cat pendant I did not wear—I had no wish to stir up further comment. Rather I placed it in the small coffer where I kept the few things I truly prized.

To my surprise Mieu, instead of treading at my heels in her usual fashion, established guard there beside the box. So she remained for most of the time we took to arrange the housing of guests.

Siggura made her choice of the ornaments Kura spread before her, a collar of gold with ruby-eyed kotti heads, bracelets of fine enamel, and a girdle of shaded agate beads—the very best of her sister’s stock, for she was always greedy. To match these she had new robes fashioned.

I saw very little of her, though I

offered formal congratulations; words which she received with the smug expression of one who had achieved what was due her.

Our guests arrived, in both families and separate companies of youths ready to display their skills and their persons. There were dome wigs worn by men who had never seen any battle, even with the raveners of the trade trails, and much time spent showing off trained oryxen, singing and dancing. So our portion of the land was awakened from its quiet by the pulsing roll of drums, the lilt of flutes, the finer notes of hand harps.

I was heartily tired of it all on the night before Siggura was to announce her choice, when festivities were at their height. Also I had had several occasions to know shame, for there had been remarks made within my hearing about the disappointment I was. There was no brightly colored clothing for me, no jewels. Even my hair knot was held only by a small silver ring. But I had sense enough not to wear the pendant, for my showing of such a treasure would be questioned.

Wearily I came to my own small house. There was a glow light on and I expected to hear Mieu’s welcome even though the singing was so loud. She always greeted me so.

Instead I heard a muffled curse and then a cry so full of pain that I threw myself within the door. My brother stood there. He was nursing his right hand with his other and I could see the blood dripping from what could only be bites and scratches of some depth.

He turned and saw me, and his face was the mask of a rat as he raised his hand to suck the blood from his wounds. My casket lay on the floor and—

There was a pitiful whine. I went to my knees and would have caught up that bundle of bloodied fur, yet was afraid to touch it lest I add to the pain which racked it. The small head raised a fraction and eyes which were filming with death looked at me. Under that head lay the pendant.

I already had my hand on the hilt of my knife when I swung around. Kalikku was backing out the door. Before I could move he hissed at me:

“Killer of kottis!”

“You—” My throat nearly burst with what I wanted to shout.

“You—there is but you and me—and who would Father believe?” He reached out his unwounded hand and caught up a flagon from the shelf near the door to hurl at me. I was not quick enough and it struck my head.

There was blackness and I do not know how long that lasted. Then I moved and was aware of the smell of the potent wine which my father had refused to have served at the feasting lest the drinking of it lead to quarrels.

I was dizzy and the world swung around me. Then I somehow got as far as my knees, holding to the stool for support. Still clinging to the stool, I edged about. My companion of little more than a happy year was only a fur bundle—unmoving.

Tears seemed to wash away the dizziness. I handled the body.

A blow, and then perhaps a kick—I felt my own lips flatten and draw back against my teeth. My tunic was wet with the wine and I jerked it off, for the fumes seemed to make my head spin the more.

I was able to think straightly again as I bunched together the sodden cloth and hurled it from me. As if it were as plain as an oft-told ballad, I knew what had happened.

To kill a kotti was death. Yet, for all his known harshness towards animals, my brother’s word would be accepted. The story was very plain—I was drunk—I stank of that very fiery wine which was supposed to arouse men to the point of insanity. I was drunk and I had killed! Was Kalikku already on his way to tell his side of the story?

Or maybe he would tell it only if he were openly accused. That I would go into later and face it when I had to. Now there was something else.

I gathered Mieu to me. That pendant seemed to catch in her matted fur. I worked it loose and would have hurled it from me for the misfortune it had caused. Yet once it was in my grasp I could not force my fingers to loose it. Instead I wreathed the chain once more about my neck.

Mieu I rolled carefully into a scarf of green which was striped with copper glitter, a fanciful thing I had bought for its color on the very first day she had come to me. Then I carried her out under the stars, speaking in a whisper the while to her essence, even though that might have fled from her. There I laid her even as she had always curled her own body in sleep, and above her I built a cairn such as we erect for those furred ones who honor us with their friendship.

Then I climbed to this point on my hut and I tasted hate and found it hot and burning, and I tried to think what life would hold for me here now, with this thing ever in my mind. Below me the guests departed and the loneliness I craved in which to order my thoughts seemed not too far away. I watched the stars and tried to be one with that which is greater than any of us.

2

The morning came with the rising fierceness of a wind. Afar I caught the warning boom of that nearest signal drum, which was always to be heeded when a storm was imminent, to raise the sand with such a flesh-scouring force that death was the answer if one were caught away from any shelter.

Below my father’s spread of house the tall cat, riven as a sentinel from the rock which formed our home territory, throbbed in answer. I was shaken out of thought, out of my self-pity, if that was what had gripped me, and hurried about my duties of seeing the stock sheltered. Even my father joined in this, and Kura, who has a particular bonding with animals and could soothe and bring to obedience a contrary oryxen or fear-savaged yaksen, was there with the others of the household all aroused by the need for haste.

Working so, I forgot all except what was right to hand and drew a breath of relief when, at the time of the second heavy drumbeat, we had all secure.

I had not approached Kalikku, nor he me, during that time. Since my father had not summoned me to face his full wrath, I could believe that my brother had not indeed told the tale he threatened. Not that that betrayal might not yet come.

The storms are capricious. Often the warnings by which we live come to naught as the whirlwind-borne sand suddenly shifts in its track. Yet never can we be sure that it will not strike. Thus we sit in what shelters we have, waiting. We strive to be one with the essence of all about us, to be a very part of the slickrock islands which support our homes and settlements and of the treachery of the sand in between. For each has a place in the whole, rock and man, wind and sand—are we not all a part of our world? Storms may last, at their worst, for days, and we in tight-held houses drink the particles which ably find their way in to film our water, grit it between our teeth as we chew on dried meat or an algae cake. It brings tears to the eyes, a gritty coating to the body, gathers in the hair, weighs upon one. Still we learn early endurance until the violent essence of the land is stilled.

This day our wait was not long, for there came the sharper note which was the signal from the distant drummer that we were not this time the chosen victims. I had spent that time of waiting sitting with the pendant in my hands trying to guess why Ravinga had gifted me with something which had brought such sorrow with it.

She had seemed to be grateful when I had discovered that foul amulet in the hair of her trusted trail beast. But her words had been cryptic, at least to me. Was I indeed not only awkward and clumsy with weapons, disliking all which seemed proper for my father’s son, but somehow thick of thought, slow of mind into the bargain?

What did give me peace and contentment? To think upon what lay about me with curiosity, to have a warm rush of excitement when I heard some song of mine echoed back as I followed a stray from our herd, to examine the varied colors of the algae, marking the subtle difference in shade against shade, to look upon the handiwork of Kura and strive to find for her those desert stones, as well as those that traveling merchants brought, which would fit in some pattern of her dreaming. She had said more than once I almost seemed to borrow her own eyes when I went trading, so well was I able to fasten upon that which served her best. This was the inner part of me—as was the friendship of beasts, the companionship of Mieu—

I had thought around in a circle and was back once more to face that which had burned its way into my mind as

a flame might burn determinedly its path. Almost I could see Mieu on her back, her four paws upheld, her eyes teasing me for a romp—or feel her soft, gentle touch of tongue tip on the back of my hand.

However, this time I was not to be left alone to chew once more on my bitterness. There was an impatient rap on the door of my small house and one of the herdsmen told me that my father wished to see me at once.

I was cold in an instant as if our sun had been struck from the sky. This then was the ending Kalikku had planned. Still I did not hesitate, but went to stand before my father’s tall battle standard which already had been wedged back into place.

There I shed my belt knife, laying it in the trough provided for weapons. My brother’s knife was there, the sullen red jewels on its hilt looking to me like the drops of blood he had shed. Also there was Kura’s, bearing the fanciful design of small turquoise pattern which she loved most. My brother, yes, I had expected him, but that Kura had been summoned—Only, of course, as a member of the house she would be there to hear the sentence pronounced upon such a criminal as I would be named.

I whistled the small call and was answered by my father’s deeper note and then I entered. He was seated on the chair fashioned of Sand Cat bones which testified to his hunter’s skill, and it was cushioned, as the floor was carpeted, with the skins of those same mighty killers.

Kalikku was on his right hand, my sister on his left, but I had more attention for my father’s face, for by its expression I might know whether I had been already judged and condemned. There was no heavy frown there, just the usual distaste I had met with for years.

“Hynkkel, there were words said among our guests which were not good to my hearing. Most were spoken behind the hand, but others more openly. You have reckoned some twenty full seasons—five since you man-banded your hair. Yet you have not soloed—”

“Let us name him ever untried boy and be done with it!” my brother said. “There is no spirit in him, as we all know.” He gazed at me as if he dared his judgment to be denied.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

Space Service Perilous Dreams

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

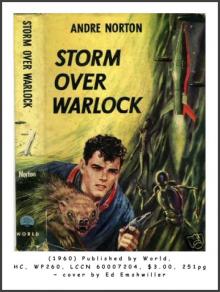

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

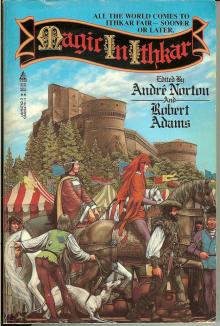

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

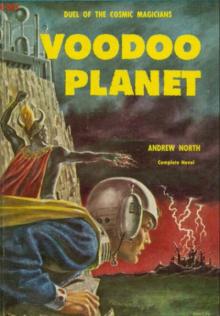

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1