- Home

- Andre Norton

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Page 28

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Read online

Page 28

Because Marsie and Kath were not the only littles down there. There were four others I had never seen before. And none of them were Up brats.

The Rhyming Man jigged around. When he stopped and they all yelled for more, he shook his head and waved his hands as if he couldn’t talk but could make motions they could understand. They all got up and formed a line and began to hop and skip after him. The floor was all laid out in squares of different colors. And, as those were stepped on, lights flashed underneath. It was as if the littles were playing a game. But I couldn’t understand it.

Then the Rhyming Man began that singing again:

Erry, Orrey, Ickery Ann

Fillison, follison, Nicholas John

Queevy, quavey, English Navy

One, two, three, out goes—

She, he, she, he, she, she, he!

Like he was shooting off a burner, he pointed his finger at each little in line. And, as he did so (it was like an Up dream), they just weren’t there anymore!

Marsie! I couldn’t jump over that balcony. I’d go splat down there, and that wouldn’t do Marsie any good, if she was still alive. But I began running along, trying to find some way down, and there was no way down. Only what would I do when I got there, because now the Rhyming Man was gone also.

Sim pounded along behind me. We were about halfway around that place—still no way down. Then I saw it ahead, and I guess I more fell than footed it down those inner stairs. When I came charging out on the empty floor—nothing, nothing at all!

I even got down and felt the squares where they had been standing, pounded on those, thinking those might be doors which opened to drop them through. But the blocks were tight. Then I began to wonder if I had tripped out like an Up—without any pills. I just sat there holding my head, trying to think.

“I saw them, they were here—then they weren’t.” Sim kicked at one of the squares. “Where did they go?”

If he saw it, too, then I hadn’t tripped. But there had to be an answer. I made myself try to remember everything I had seen—that crazy song, them marching, and then another crazy song—

I stood. “They got out somehow. And if there’s a door it can be opened.” I couldn’t just be wild mad, I had to think, and straight now. No use of just wanting to grab the Rhyming Man and pound his head up and down on the floor.

“Listen here, Sim. We’ve got to find out what happened. I’m staying here to look around. You cut back and get the rest of the guys, bring them here. When he comes out, I want that Rhyming Man!”

“Staying here by yourself mightn’t be too good an idea, Lew.”

“I can take cover. But I don’t want to miss him when he comes back. Then I can trail him until you catch up.” It might not be too bright, but it was the best plan I had. And I intended going over that flooring until something did happen and we could find the way in to wherever Marsie and the rest of the littles were.

Sim went off. I knew he was glad to get out of that place, but he’d be back. Sim had never back-footed yet on any mission. Meanwhile, I’d better get busy.

I closed my eyes. Sometimes if you think about a thing hard enough you see it like a picture in your mind. Now—the six littles—and then, in front of them, the Rhyming Man jiggling back and forth, his suit all bright and shining—singing about London Bridge—

Opening my eyes again I studied the blocks. The littles had been sitting, or squatting, there, there, and there. And he had been over there. I raised my hand to point as if I were showing it all to someone else.

London Bridge? London was another city—somewhere—not near here. When the cities were all sealed against the bad air—well, for a while they talked to each other with T-casts. Then it wasn’t any use—everyone had it all just as bad.

Cities died when their breathers broke—those that had been the worst off in the beginning. In others—who knows what happened? Maybe we were lucky here, maybe we weren’t. But our breathers had kept on going—only the plagues hit and people died. After all the oldies died, there was a lot more air.

But London was a city once. London Bridge? A bridge to another city? But how could one step off a block onto a bridge you couldn’t see, nor feel? Silver and gold—we wore silver and gold things—got them out of the old stores. My tick was gold.

The whole song made a kind of sense, not that that helped any. But that other thing he had sung, after they had moved around on the blocks—I closed my eyes trying to see that march, and I moved to the square Marsie had stood on right at the last, following the different-colored blocks just as I had seen her do.

Yeah, and I nearly lost my second skin there. Because those blocks lit up under my feet. I jumped off—no lights. So the lights had meaning. Maybe the song also—

I was almost to the block where the Rhyming Man had been, but before I reached it, he was back! He was flashing blue and gold in a way to hurt your eyes, and he just stood there looking at me. He had no stunner, nor burner, not even a pricker. I could have cut him down like a con-rat. Only if I did that, I’d never get to Marsie, I had to have what was in his mind to do that.

Then he gave me one of those bows and said something, which made no more sense than you’d get out an Up high on red:

Higgity, piggity, my black hen—

She lays eggs for gentlemen.

I left my pricker in my belt, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t take him. I’m light but I’m fast, and I can take any guy in our crowd. It’s mostly thinking, getting the jump on the other. He was still spouting when I dived at him.

It was like throwing myself head first into a wall. I never laid a finger on him, just bounced back and hit the floor with a bang which knocked a lot of wind out of me. There he was, standing as cool as drip ice, shaking his head a little as if he couldn’t believe any guy would be so dumb as to rush him. I wanted a burner then—in the worst way. Only I haven’t had one of those for a long time.

One, two, three, four,

Five, six, seven.

All good children

Go to Heaven.

One, two, three, four,

Five, six, seven, eight,

All bad children

Have to wait.

I didn’t have to have it pounded into my head twice. There was no getting at him—at least not with my hands. Sitting up, I looked at him. Then I saw he was an oldie—real oldie. His face was all wrinkled, and on his head there was only a fringe of white hair, he was bald on top. The rest of him was all covered up with those shining clothes. I had never seen such an oldie except on a tape—it was like seeing a story walking around.

“Where’s Marsie?” If the oldie was an Up, maybe he could be startled into answering me. You can do that with Ups sometimes.

One color, two color,

Three color, four,

Five color, six color,

Seven color more.

What color is yours?

He pointed to me. And he seemed to be expecting some answer. Did he mean the block I was sitting on? If he did—that was red, as he could see for himself. Unless he was on pills—then it sure could be any color as far as he was concerned.

“Red,” I played along. Maybe I could keep him talking until the guys got here. Not that there was much chance in that; Sim had a good ways to go.

You ‘re too tall,

The door’s too small.

Again he was shaking his head as if he were really sorry for me for some reason.

“Listen,” I tried to be patient, like with an Up you just had to learn something from, “Marsie was here. You pointed at her—she was gone. Now just where did she go?”

He took to singing again:

Build it up with stone so strong,

Stone so strong, stone so strong.

Hurrah, it will last ages long—

Ages long, ages long—

Somehow he impressed me that behind all his queer singing there was a meaning, if I could only find it. That bit about my being too tall now—

“Why am I too tall?” I asked.

A.B.C.D.

Tell your age to me.

Age? Marsie was a little—small, young. That fitted. He wanted littles. I was too big, too old.

“I don’t know—maybe I’m about sixteen, I guess. But I want Marsie—”

He had been jiggling from one foot to the other as if he wanted to dance right out of the hall. But still he faced me and watched me with that queer “I’m-sorry-for-you” look of his.

Seeing’s believing—no, no, no!

Seeing’s believing, you can’t go!

Believing, that is best,

Believing’s seeing, that’s the test.

Seeing’s believing, believing’s seeing—I tried to sort that out.

“You mean—the littles—they can believe in something, even though they don’t see it? But me, I can’t believe unless I see?”

He was nodding now. There was an eager look about him. Like one of the littles playing some trick and waiting for you to be caught. Not a mean trick, a funny, surprise one.

“And I’m too old?”

He was watching me, his head a little on one side.

One, two, sky blue.

All out but you.

Sky blue—Outside! But the sky hadn’t been blue for years—it was dirty, poisoned. The whole world Outside was poisoned. We’d heard the warnings from the speakers every time we got close to the old sealed gates. No blue sky—ever again. And if Marsie was Outside—dying!

I pointed to him just as he had to the littles. I didn’t know his game, but I could try to play it, if that was the only way of reaching Marsie now—I had to play it!

“I’m too big, maybe, and I’m too old, maybe. But I can try this believing-seeing thing. And I’m going to keep on trying until I make it work! Either that, or I turn into an oldie like you doing it. So—”

I turned my back on him and went right back to that line of blocks up which they had gone and I started along those with him watching, his head still a little to one side as if he were listening, but not to me. Under my feet those lights flashed. All the time he watched. I was determined to show him that I meant just what I said—I was going to keep on marching up and down there—maybe till I wore a hole through the floor.

Once I went up and nothing happened. So I just turned around, went back, ready to start again.

“This time,” I told him, “you say it—loud and clear—you say it just like you did the other time—when the littles went.”

At first he shook his head, backed away, making motions with his hands for me to go away. But I stood right there. I was most afraid he would go himself, that I would be left in that big, bare hall with no one to open the gate for me. But so far he hadn’t done that vanishing bit.

“‘Orrey,’” I prompted.

Finally, he shrugged. I could see he thought I was heading into trouble. Well, now it was up to me. Believing was seeing, was it? I had to keep thinking that this was going to work for me as well as it had for the littles. I walked up those flashing blocks.

The Rhyming Man pointed his finger at me.

“Erry, Orrey, Ickery Ann.”

I closed my eyes. This was going to take me to Marsie; I had to believe that was true, I hung on to that—hard.

Fillison, follison, Nicholas John.

Queeuy, quavey, English Navy

One, two, three—

This was it! Marsie—I’m coming!

“Out goes he!”

It was awful, a twisting and turning, not outside me, but in. I kept my eyes shut and thought of Marsie and that I must get to her. Then I fell, down flat. When I opened my eyes—this—this wasn’t the city!

There was a blue sky over me and things I had seen in the T-casts—grass that was still green and not sere and brown like in the last recordings made before they sealed the city forever. There were flowers and a bird—a real live bird—flying overhead.

“Amazing!”

I was still on my knees, but I moved around to face him. The Rhyming Man stood there, but that glow which hung around him back in the hall was gone. He just looked like an ordinary oldie, a real tired oldie. But he smiled and waved his hand to me.

“You give me new hopes, boy. You’re the first of your age and sex. Several girls have made it, but they were more imaginative by nature.”

“Where are we? And where’s Marsie?”

“You’re Outside. Look over there.”

He pointed and I looked. There was a big gray blot—ugly looking, spoiling the brightness of the grass, the blue of the sky. You didn’t want to keep looking at it.

“There’s your city, the last hope of mankind, they thought, those poor stubborn fools who had befouled their world. Silver and gold, iron and steel, mud and clay—cities they’ve been building and rebuilding for thousands of years. Their bridge cities broke and took them along in the destruction. As for Marsie, and those you call the littles, they’ll know about real stone, how to really build. You’ll find them over that hill.”

“And where are you going?”

He sighed and looked even more tired. “Back to play some more games, to hunt for more builders.”

“Listen here,” I stood up. “Just let me see Marsie, and then I’ll go back, too. They’ll listen to me. Why, we can bring the whole crowd, Bart’s, too, out—”

But he’d started shaking his head even before I was through.

“Ibbity, bibbity, sibbity, Sam.

Ibbity, bibbity, as I am—” he repeated and then added, “No going back once you’re out.”

“You do.”

He sighed. “I am programmed to do just that. And I can only bring those ready to believe in seeing—”

“You mean, Sim, Jak, the others can’t get out here—ever?”

“Not unless they believe to see. That separates the builders, those ready to begin again, from the city blind men.”

Then he was gone, just like an old arc winking out for the last time.

I started walking, down over the hill. Marsie saw me coming. She had flowers stuck in her hair, and there was a soft furry thing in her arms. She put it down to hop away before she came running.

Now we wait for those the Rhyming Man brings. (Sim and Fanna came together two days ago.) I don’t know who he is, or how he works his tricks. If we see him, he never stays long, and he won’t answer questions. We call him Nicholas John, and we live in London Bridge, though it’s not London, nor a bridge—just a beginning.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

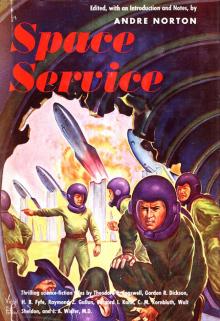

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

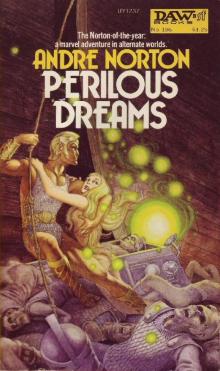

Space Service Perilous Dreams

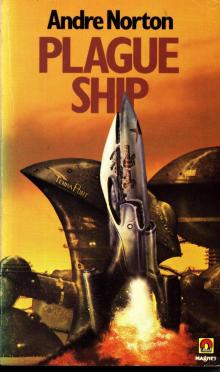

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

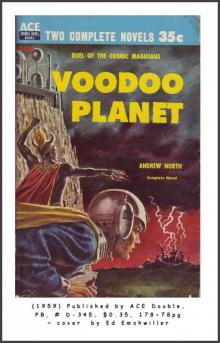

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

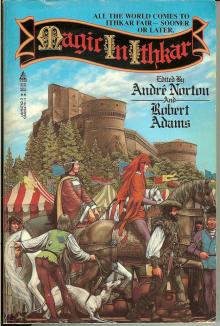

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

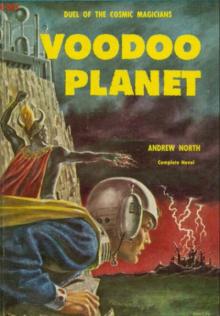

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1