- Home

- Andre Norton

The Key of the Keplian Page 4

The Key of the Keplian Read online

Page 4

Eleeri blinked. “Are there still trails?” Then she snorted at her own stupidity. “Of course there must be; otherwise you wouldn’t have been able to get back. How does the land lie there?”

She watched as he drew a burned stick from the fire and drew on the stone floor. “I see,” she finally said. “If I return along the mountain edge to the west and cross north, then I’ll be in Estcarp.” She laid a slim finger on the blank portion. “What land lies here?”

Cynan was silent for a long time. When he finally answered, she was conscious of a rising desire. There was something in the name of Escore as he said it, something which drew her even as the east had originally drawn her here to this secluded valley. She studied the map silently before she spoke.

“Our river—if I followed that, I would arrive in time in this land?”

“So I think, but I do not know for certain.”

Eleeri stood and walked to her bedding. She hauled firewood, banking the fire for the night as she thought. The pull, the feeling of rightness grew stronger. She settled into her bedding and allowed her body to relax.

From his bed the old man watched her face. Just before sleep claimed them, he spoke again. “You’ve decided, haven’t you?”

“Yes. When spring comes, I will go to Escore. Will you come with me?”

“No. I was born here in this hold. I came back to die here. But if you meet any who knew me where you go, tell them I still live.”

“I will.” She drifted into sleep then. A destination determined. Escore . . . she would go to Escore.

3

The winter was both a time of friendship and a time of hardship for Eleeri. Cynan taught her all the scraps of languages he had picked up over a long busy life. To that knowledge he added warnings, hints, and beliefs about the places of the Old Ones, their natures, and beginnings. His mother had possessed some small gifts, so that the girl’s increasing abilities failed to distress him as they might have another. The girl herself barely noticed that her gift was growing, stretching as she used it. She had always had the horse gift; it was a part of her.

But in the clear air of this new land, things were changing. Before she had been able to handle the wildest mare, soothe the most savage stallion. Foals had run to her for comfort. By the time she’d reached seven or eight, Far Traveler had been using her to start the training process for the horses he accepted. Beasts trained by her seemed to be calmer, more intelligent and sensible. Eleeri had loved the work but hated it when each four-footed friend left again. She knew that all too many owners would treat them as cheap machines.

She loved horses, the feel of hard muscle sliding under her hands as she groomed. The rough strands of mane, the scents and the sounds. But she loved most of all the feeling of communion she had with them, their trust and returned affection. Over that winter she did not regard it as odd that this communication deepened. It had been rare for her to keep a horse past the few weeks necessary to explain their new duties to humans. With these three she had spent much time and many months. Of course they had responded. But Cynan, watching, knew that it was far more. There were times when it was as if the minds of girl and horse mingled so that beast and rider were one.

He deliberately moved onto that subject one night. “Eleeri, the power often comes as it will and not as you will it.” She glanced up, but said nothing. “You say that in your own land none have great power, only small gifts that tend to lessen with each generation.” The girl nodded. “Then think on this. Here it is not so. It may be that here the gift you have grows. I do not believe it is so small as you think, and such gifts untrained can be dangerous. If you come upon anyone who can, let them teach you.”

“Look, I don’t think I have the power you do. But”—she looked up and smiled, a smile of affection for the old warrior—“I promise I’ll get teaching if I can find a willing teacher. And”—she held up a hand before he spoke—“I’ll make sure this one is of the Light before I begin to learn, okay?”

“Okay.”

Cynan returned to the shirt he was mending and Eleeri to the deerskin trousers she was making. Over the autumn she had hunted well, and not a hide or fur had been wasted. The quiet isolation of winter was a time for using these. She planned to leave Cynan a complete set of the deerskin garments along with a fur cloak. She knew that nowadays his old bones ached in the cold. She also planned to make a pair of special knee-high moccasins for him. The hide under the foot was to be triple-layered and the moccasins would be fur-lined. That would keep his feet warm and dry when he must go into the snow to tend the beasts next winter.

She glanced at him from the corner of her eye. It would not be easy to leave. But he would be furious if she stayed. He would know it was to look after him, and his pride would be cut to the heart. She understood the pride of a warrior. She would not wound the old man by counting him as less than he was. He had come back to this place which had once been his, to die. They both knew it. Here in a tiny graveyard higher into the hills lay the bodies of his wife and last child. The bodies of his parents, and his siblings. The hold had been the refuge for his bloodline for so long, the years faded to dust.

Her mind wandered to his words. She wasn’t sure . . . perhaps her gift was growing stronger. But why should she have any great gift at all? It was true that there had been medicine men and women of ability in Far Traveler’s line. Too many times she had been forced to bite down on hot words as her schools decried those gifts, calling them native superstition. Something snagged on her thoughts and she dimly recalled the teasing that her grandfather had given his wife. Yes . . . she concentrated, and the memories grew a little clearer.

They had been around the table: her mother Wind Talker, her father, and his parents. It was on one of her grandparents’ rare visits to Eleeri’s home. Her grandfather had been speaking of Cornish superstitions and their use.

“. . . a method of control in many cases.”

“Then you don’t think there was ever anything more?” That had been her mother.

“Not to denigrate your beliefs, my dear, but no, I don’t. I think that it was usually a way to handle large numbers of people. To persuade them into suitable actions. For instance, in New Zealand a tapu may be placed on shellfish to allow the numbers to recover after a bad season. The people believe they will be cursed if they touch them until the tapu is lifted. In this way their elders control them and the food supply.”

He had suddenly chuckled. “If I believed all the old talk, I’d never have married your mother-in-law.”

His son moaned. “Not that old tale again, Dad.”

But Wind Talker was interested. “Is there some story?”

John Polworth leaned back, coffee cup in hand. “Story, that’s all it is, but it does show the power of superstition. Your mother was a Ree before I wed her. The old folks said that was an uncanny line. Reckoned that a long time ago the women had been priestesses of another faith and that it was bad luck to wed them. Jane’s great-grandmother was Jessie Ree. They said she could call storms or calm them if they came. Lot of rubbish, but my folks didn’t want me to wed Jane.”

Wind Talker leaned forward. “But you married her despite this.”

“I did indeed, my dear. I’ll have no truck with such nonsense, and so I told them. Jane Ree is the one I want and that was my last word on the subject.” He drank from his cup and set it down again with a decisive thump.

His wife smiled at them. “It certainly was his last word. But his parents never quite accepted me until John said we were leaving. He’d had the offer of a good job across the water, and maybe the people there would care less about superstition and more about the fact he loved me and I was a good wife. So we came and we’ve never regretted it.”

Eleeri sat, remembering the feeling of warmth and love that had surrounded her then. In later years she had heard other reasons for the hasty departure of the Polworths from Cornwall to their new country. A war had been coming, and John Polworth had no time for war

. It didn’t fit into his plans, to die fighting in a country far from his own, for a cause he was not sure he believed in. So he’d married Jane swiftly and accepted the promised job in America. By the time war touched the United States also he was in a reserved occupation. She might have scorned him as a coward. But Jane knew it had not been that alone. He would have been no use as a fighter and he knew it.

She wondered if he had ever regretted his decisions. He had loved his wife, that had not been in doubt. He had appeared happy in his work and country, too. But did he ever wish to be back on his rock and seagirt land? She shrugged. Perhaps he’d had a wish when he knew in that last few seconds that he and Jane were about to die.

It was strange that both her parents and grandparents had died in accidents. It had been the year following that night around the table. A vacation, a crashed plane—and among the dead, the names of her grandparents.

Her parents had been killed in a car crash the year after that, when she was nine. For a whole six months she had lived—derided, despised, and humiliated—with the Taylors, her aunt and uncle. Finally she had fought back with a smuggled letter to Far Traveler. But before he could come, her uncle had caught her releasing a horse he was breaking. She could not have helped herself; the animal’s weary pain and confusion had cried out to her beyond refusal. But it had happened before. He was a man of quick and brutal temper and she was the despised Indian. He had beaten her far more savagely than he had intended, but it had saved her in the end. Far Traveler had come that afternoon.

Her relatives had made the mistake of refusing to allow him entrance. But with the rise of Indian rights and consciousness this had been more foolish than they had realized. Her great-grandfather had gone to find a man he knew. This one had spoken to others, and Far Traveler had returned with support. She had been brought out and, partly from the pain of her beating, partly with the knowledge that this might be a way out, had fainted within the circle of adults. Action had been swift after that.

She had been discussed, questioned, and refiled. Far Traveler had accepted her into his home, and certain friends had stood surety that she would be cared for. She might even have believed herself to have been safe, beyond the malice of a man steeped in hatred of her race, but for that last glimpse of him as she was taken away. He had watched, eyes bright with hatred. A long measuring look said that one day he would have his chance to pay her back for this humiliation. She had known that once Far Traveler died there would be no refuge. The Taylors would take her back, aided by social services people who would believe it was best for her.

She guessed that the years after that only distilled Taylor’s hatred. That in the time before she reached sixteen he would be able to build a cage of lies that would entrap her, perhaps forever. She had made her choices, and freedom beyond hope had been the result. Maybe Ka-dih, Comanche god of warriors, had watched over her.

She now bent to her work again. Maybe the blending of the two bloodlines had each strengthened the gift. She knew her people had often had the horse gift, but hers was stronger by far than usual. She shrugged again. It was hers; the how no longer mattered.

Across the fire Cynan watched her, unnoticed. Firelight glinted on the high cheekbones, the aquiline planes of her face. The gray of her eyes turned to black in the shadows and the black of her hair to night. She looked to be slight with the long fine boning typical of his own race, but he had seen the strength under that deceptive appearance. The girl was a warrior. He’d spent much time teaching her sword drill, but even he could teach her nothing she did not already know with bow and knife. She moved with apparent slowness, the smooth motion deceiving the eye. In reality she was swift, fast-reflexed, and controlled.

From things she had let slip it would seem that her kinsman had trained her almost half of her life. You’d have thought the man had known where she would go, what choices she would make. Cynan smiled to himself. In all probability it had only been an old man’s memories. The girl had been taught as Far Traveler had been in his own distant youth. In teaching the child, he had unconsciously returned to the days when life was simpler for his people. But in so doing, he had given her an excellent education for the world she now found herself in. Maybe the gods had had a hand in it after all.

His eyes touched her with affection. She was a good child, kind and generous. He must persuade her to leave as soon as the path was clear. If she stayed too long after that, she would discover his secret. It had been only her aid that had brought him through this winter. If she realized this, she might choose to stay. He would rather that she left believing him to be alive behind her. And so he would be, through the spring, the summer, and into the autumn. But he could feel the knowledge deep inside himself. As the year faded into the death season, so would he. Before first snows he would be gone. He smiled; it was time.

But he would not have her here mourning over his body. He’d seen the pain the death of her kinsman still caused her. Let her ride out knowing she’d left him well prepared for next winter. As the last days of next autumn faded into the land, he would seek out the graves of his loved ones. There he would lie down and pass to join their spirits. He would not have the child there to grieve when it happened. Nor would he have her live the next winter alone in a deserted hold.

His mind wandered. The horses: he needed none of them; she must take the three. He wished to give her a leave-taking gift, too.

He rose quietly and strode up the ancient stone stairs. He’d given almost everything of value to his far kin before he returned here. One thing yet remained. He pressed a stone in the wall, caught at the edge as it swung out. Within was a tiny casket carved of a glowing golden wood. Fingers fumbled at the catch, then the lid rose to release a sweet scent and a soft flare of light. He chuckled softly. Of all the things he could have kept, it had been this one. It would weigh nothing; she had enough weight to carry. But that she would love this he knew; it was right for her. Perhaps Another had a hand in this, too.

He replaced the stone and returned to his mending. When the time came, he would be ready. In the meantime, it would be well if the child also learned to write at least one language in this world that was new to her. He rose again to fetch what he needed.

“What are you up to now?” Eleeri asked him. “You haven’t sat still for a minute this evening.”

Cynan looked at her thoughtfully. “There are several things I know which may help you in days to come. Two I could teach you while winter keeps us inside this hold: one is reading in the tongue of Estcorp; the other is signing.”

Eleeri jerked upright, her eyes suddenly alert. “Your people have a sign language?”

Cynan smiled. “I see yours do also. Ours developed only with the need to fight. Oh, hunters had always held some signs in use. But when we rode to war and as scouts, the language developed greatly. You learn well and quickly. If your people also had such a language, I think you would have no trouble learning ours.”

“Then I will, and I’d like to try reading as well. My great-grandfather always said that one should learn if any were willing to teach, that knowledge was never wasted.”

“He was a wise man,” Cynan commented. “Come, sit beside me and I will show you the signs. After that . . . I have only one book, but you will learn well enough with that to read.”

The winter moved on slowly, and at last the thaw started. With many months to study, Eleeri could now sign in the simple language of hunting and war as well as any born to this variation. She could also read, albeit with some stumbling over unfamiliar words.

By now she was more than ready to ride. Furs and skins had all been made into stout clothing. Saddles and horse gear were mended and oiled. She would use the horses in turn to hunt, as yet they were unfit for a long trail.

Water trickled down the stones of the hold, dripped miserably from the roof, gathering in deep sticky mud in doorways. Eleeri heaved a sigh. She hated that, but it would all pass when the weather warmed further.

It did

so, and to her surprise, Cynan insisted on coming out to ride once the land had dried.

“The mud has gone and my bones no longer ache so much.” He smiled at her. “Besides, there is something I would show you.” He refused to say more, leading her deep into the hills as her sturdy pony obediently followed the tail of Cynan’s mount. They rounded the bend to find themselves in a small cup of flat land. Most of it was taken up by . . .

“The place of the Old Ones you told me about?”

“Even so, my child.” He dismounted laboriously. “Sit here on the grass and listen.” He waited until Eleeri was settled comfortably. “My people worship Gunnora. She is the Lady of fruit, grain, and fertility. Lady of love and laughter. In her name we celebrate the change of a girl into womanhood. The amber pieces you showed me are of great worth. They contain seeds and could be sold as amulets of her symbol. I think they did not come to you by accident. Guard them well. Do not show them to others, but if you can, pray to Gunnora at need.”

Eleeri considered that. It sounded as if this Gunnora was the same as the Corn Woman, goddess to many Indian tribes. She would feel no sense of wrong in praying to Corn Woman under another name.

“I can do that, and I’ll cherish the amber. What else?”

“In Escore and on your journey there will be danger. Not only from beasts and man, but also from creatures of evil. They could imperil more than your body. I would ask of those who built this place if they will grant you guards.”

The girl blinked. Was he going to ask for ghost guard dogs or magic swords?

Cynan saw her confusion. “You have seen me place the small pebbles I carry about the doors. Those are guards, in a way. While they lie in any entrance, nothing which is of the Dark can enter. Men who are wicked, that is another thing,” he added as both remembered the bandits.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

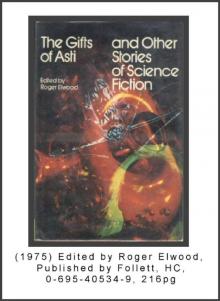

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

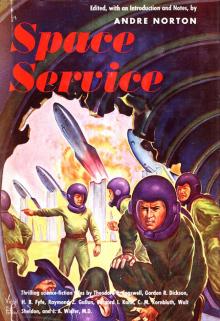

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

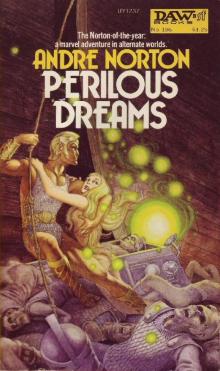

Space Service Perilous Dreams

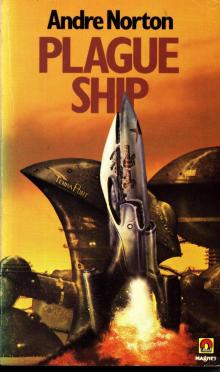

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

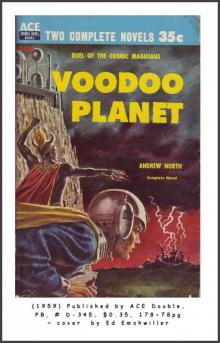

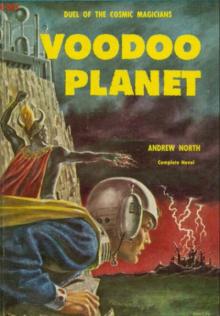

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

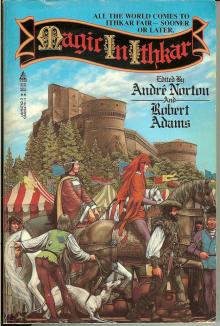

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1