- Home

- Andre Norton

Wheel of Stars Page 5

Wheel of Stars Read online

Page 5

Friendly as Lady Lyle had been and as pleasant their relationship, Gwennan was well aware that barriers existed—ones she did not dare to try to pass. She was always in awe of the older woman and she felt too gauche and young to presume.

So now she finished breakfast, put the house to rights, and set out for the center of town as the sun arose to full day. It was colder and she wondered how far away was the first snow of the season. Winter closed in hard at times—tightly if a blizzard came. They might not have to be as self-sufficient as the people on farms or along the coastline where the full force of storms hit, but still winter was to be taken seriously.

She had never considered before that Miss Nessa’s house was unduly isolated. In fact Gwennan had enjoyed the sense of space about it. Now—no, she was not going to let herself be intimidated by the events of the past night. And, even if she wanted to move—there were no quarters available in town. The motel by the highway closed at the end of the tourist season and there were no places to board that she knew of. She had the phone and, if she felt in any way uneasy, she could go to the Newtons.

Moving briskly against the wind Gwennan reached the library, unlocked the door and went to shed her outer wraps. There was a measure of warmth already. James Quarles kept a good eye on the furnace. Returning to the large front room she stood looking out at the center green of the village. It was then that she saw Mr. Stevens come from the white house of the southwestern corner. It was early for him to be on his way to his office. No, he was not going in that direction at all—rather he cut across the open heading straight for the library.

Why here? He was on the board, of course, but Gwennan could not account for any emergency to bring him visiting now.

“Saw you on the way in.” He spoke without any formal greeting, quite unlike his usual way. “Knew you would want to know. She called me last night—Lady Lyle that is. Seems she has been taken worse—they want to see her down at the hospital in the city—then perhaps fly her west to some big clinic. There’s a doctor there she’s gone to before. She said to tell you goodbye. But I’m afraid,” he looked troubled, “she was very weak when I saw her yesterday—had a number of things all docketed and ready for me to take care of. Looked really bad. But she has a lot of confidence in this man she is going to see.”

“Did—did she leave an address?” Why had the maid called Gwennan merely to cancel a visit and not Lady Lyle herself to say goodby? Maybe—maybe this was proof that their relationship had never been as she thought, wanted, that they were real friends—or beginning to be so. There was a feeling of emptiness, of loss, which hurt. “I—might write.”

“She gave me none for now, no. Said she would be in touch as soon as she could. But she certainly has taken a liking to you, Gwen—first time she ever showed any interest in any one around here. And she made me promise to tell you as soon as possible.” He eyed her now, Gwennan thought, as if he were wondering what the mistress of Lyle House could ever have seen in her.

Then he nodded. “That’s it. I’ll let you know when I hear any more. Or she may get in touch with you when she is settled.”

“Yes—” Gwennan agreed, though inwardly she was more than a little dubious about that.

4

Gwennan hurriedly washed her hands. There would be a library story hour in twenty minutes, and she had spent far too much time in the storeroom shifting the contents of dusty boxes in which loose papers, magazines, notebooks and pamphlets—time-browned and fast-disintegrating material—had been mingled. What pertinent information she had managed to dig out of this remnant of the town’s past was scrawled on a single notebook page.

Sam Grimes’ “Black Devil” tale had sent her here to explore the Crowder bequest. Old Mrs. Bertha Crowder had died five years ago, and, as the last of her family, she had willed their collected papers—four boxes full to the brim—to the library. These had arrived during Miss Nessa’s last days, to be simply dumped in storage as there had been no time for sorting. Since then Gwennan had forgotten them until now.

The Crowders had, off and on, for several generations acted as town clerks, keeping meticulous records, according to Miss Nessa. Her judgment had been correct. Here Gwennan had uncovered not only the visit of the “Black Devil” Sam had spoken of, but two hints that it had been known before that time within the valley.

Regretfully she had no more time today to burrow. Instead she hurried upstairs. The library building was really the old Pyron house, one of the first built in the town. Some partitions had been removed when it had once served first as the town meeting house, then as a church when the original had burned down in the 1880s. The rooms remaining were now oddly shaped with alcoves and unexpected corners, and in winter the light was limited. So far, in spite of Gwennan’s several petitions to the board, there had been no more lamps added.

Before those shadowed corners had only been an annoyance. Now, to her self-disgust, she found herself glancing at them only too often—listening—especially when there were few patrons and she was alone. This afternoon she was even looking forward gratefully to story hour with its inflow of noise and confusion.

Two mothers, looking harassed, brought up the rear of the children’s line today, and Miss Graham herself was frowning. She caught Gwennan at the end of the story time and spoke hesitatingly, as if she did not know quite how to express what she deemed herself duty bound to say.

“We won’t be coming on the 30th. There are going to be the new school hours starting that week—”

“New hours?”

“Yes. The parents out on Spring Road and Hardwick Trace are objecting to the early morning hours for the bus—especially now when the mornings are dark—also they want the children home as soon as possible in the afternoon. They had a meeting with Mr. Adams and decided best to change the schedule. That will curtail a lot of our extra activities this term.”

“Yah—we don’t want that old devil to get us—” Thaddy Parker came up behind Miss Graham. “My pop says we gotta be in ‘fore dark these days. That old devil—he sure chewed up the Haskins’s chickens!”

“That is enough!” Miss Graham possessed the now-nearly out-of-date ability to subdue with a look and tone of voice the near unsubduable. Thaddy withdrew quickly.

“It is only a panther, of course,” the teacher said. “But the story has grown so you would think that we are being stalked by a whole pack of bloodthirsty tigers. And I cannot deny that the parents have a right to be upset after what happened at the Haskins’s.”

“What did happen?” Gwennan had been so wrapped in her own research for the past day and a half that suddenly she felt as if she had been completely shut off from news. In the village rumor and news spread so quickly she could not understand how she had missed this.

“Some animal got into their big chicken house—you know they’ve gone in for egg production this past season—send most of their eggs on to that new frozen dinner place up at Fremont. It was not pretty what happened. I gather from what I heard that most of the fowl were just wantonly torn apart in a most ghastly way. Also the eldest Haskins boy found a deer at the edge of their largest cornfield treated in the same way. I wonder if the creature responsible is not rabid.

“Oddly enough when they tried to put the hounds on the trail they utterly refused to follow it. And now there’s all kinds of stories about—concerning some old legend.”

“I know—the Black Devil.”

“What did you see the night of the storm?” Miss Graham eyed her narrowly. Gwennan was not surprised, undoubtedly the story of how she called Ed was now all over town, perhaps even spread throughout the county—helping to feed this uneasiness.

“Not very much—it was so dark, you know. Just something big and black at my window.” There was no use in adding her terror at the sighting.

“And with you living alone!” Miss Graham shook her head. “Don’t you question the wisdom of doing that now?”

“Not yet.” Gwennan summoned a smile. “But I must admit that my

phone line is really hot these days—with all the calls I have been having. As for the Devil—I have no chickens to tempt him. I’m sure that you are right—that it is a panther—maybe a sick one. Sooner or later it will be shot and then everything will settle back to normal again.”

Only Gwennan could not banish her thoughts so easily. There was too much in this present situation which paralleled not only material in the books she had read (black dogs, devils, fearsome creatures sighted sometimes in the midst of hard electrical storms) but also in the cryptic notes she had taken earlier this day. The memory of the evil which those red eyes had appeared to project was something she could not even try to explain to anyone else—and that vile odor—.

Could such stench accompany any known animals? Was what she had half seen the same thing which had raided the Haskins’s farm? The evidence was too like the accounts in books—though she would not have suggested that to any one in town.

As she closed and locked the library door a little later, Gwennan was startled by a figure stepping abruptly out from behind a big stand of now leafless lilac bushes to join her.

“Miss Daggert—”

Gwennan hoped he had not marked her frightened start. “Mr. Lyle. Oh, have you heard from your aunt?” That was the only reason she could guess for his seeking her out.

“Saris? No, I have not heard from her. Were you expecting a message?” His voice sharpened.

“No. But I had heard that she is ill. Naturally I am concerned—”

“Naturally,” once more mockery tinged his tone. “I am not a messenger. Rather—perhaps you might consider me a bodyguard. There is a Black Devil abroad, you know. In fact I believe you already had a personal reason to be able to authenticate its existence. And you do have a lonely walk home. One it might not be too safe to take alone.”

“It is one I have made twice daily for most of my life,” Gwennan returned, unable to keep a tinge of tartness out of that answer. She had no wish to ever admit to Tor Lyle that she had any fears. Though during the last few moments before she left the library she had been recalling too many dark places along that road as well as the relative distances between one house and the next.

“Ah, but that was before the Devil made his entrance. Tell me, Miss Daggert, what theory do you support—that this is a rabid panther on the loose? Or something else—perhaps out of the past?”

She moved on at a faster pace than usual as he fell into step beside her. Short of manufacturing some errand in the village, she had no way of escaping company she did not want and yet could not refuse without appalling rudeness.

“I have no idea what it might be—”

“Now a panther,” he continued, “should, I am sure, have left some more identifiable tracks—at least at your house after the rains. Of course, a Devil, not being of our world could proceed without any tangible traces—should it wish to. For example, soon after the first settlers arrived in this valley there was a blacksmith named Haskins (how these family names do linger on) who lost a particularly valued ox to something which literally tore the unfortunate animal into bits. A day or so later he himself was chased in the woodland for some distance by something he was never afterwards able to describe. Mainly because the poor fellow fell into what was described as a fit and ever after wandered in his wits.

“Again—in 1745 a party of French and Indians coming down on a raid were completely routed and one of the Frenchmen killed with the same type of wounds as the ox had shown. His comrades fled, and no one of the enemy ever ventured in this direction again. But the Devil prowled around for several weeks and killed two cows—as well as drove an old woman into nearly the same state of imbecility as Haskins had suffered. Oh, yes, apparently the Devil does make a habit of visiting this section of the country from time to time.”

“It sounds as if you have been researching the subject,” Gwennan answered. She had her bits and pieces out of the Crowder papers but it would seem that Tor Lyle also had access to information even more complete.

“Oh, we’ve kept records of the valley ourselves. I think it amused many of the Lyles to write diaries and such. There are a goodly number of them to hand if one wishes to go legend-seeking. How about you, Miss Daggert, would you like to come up to the house and help me delve into the past? I do not know whether we could uncover anything pertaining to the present case—but it might amuse you. Tomorrow is Saturday, and I believe you close the doors of your library at noon. Will you be my guest for lunch and let me show—”

“No.” Her refusal was short and pointed. It was not until she made it that she realized how rude that short answer was. Though inwardly she did not want to qualify it, she made herself add:

“Tomorrow is the monthly meeting of the library board. I have a report to present.”

“Then on Sunday—” he began in the same lazy, half teasing voice.

“On Sunday there is church, then I am to have dinner with Miss Graham and her mother.”

“Which brings us—”

“Mr. Lyle, I am going to be frank. I have no intention of again visiting Lyle House until I am asked by your aunt.”

She seemed to have silenced him. Though there was still a shadow of smile about his lips. Then, after a moment which Gwennan was sure he deliberately prolonged to make her feel more uncomfortable, he said:

“You are running, you know, and you have not a single chance of winning. I can show you things which would surprise you—things to change completely this narrow, tight, dull little world of yours. You will begin to learn them sooner or later anyway but it would be better if you accepted me as a guide—decidedly better—and perhaps—safer—”

That uneasiness she always felt when he was near was fast becoming irritation. “I am not interested. I wish you would understand that—I am just—not interested!” She did not have the courage to blurt out that she did not like him, that he made her uncomfortable, and that the less she saw of him the happier she would be.

“But you will be. Thus when the time comes that you understand just what this is all about—well, just let me know.”

Gwennan shook her head stubbornly. Since he made no move to leave her in spite of her open antagonism, she strove to find another topic of conversation—one which would not lead back to devils, history, or anything of the sort. There was an air of self-satisfaction in his manner which jarred, made her feel that perhaps she was handling this situation poorly.

“Where did Lady Lyle go—is she in a hospital? I would like to write to her—”

“You will discover, if you do not already suspect, that Saris is a woman of whims. She has a number of places where she has established retreats in the past, when she felt that the world became too dull. Now she is doubtless basking comfortably in one of them.”

“But she is ill!” Gwennan protested. Certainly he was not acting as might any concerned relative.

“Saris is well, or ill, or whatever she pleases, when she pleases. My young friend, you must not ever count on Saris’ interest lasting. She has always been one to take a sudden liking to a person, play at being friends, and then drop that acquaintance when she becomes bored. And Saris is, I can testify, most easily bored. A plea of illness is always the perfect unanswerable excuse—do you not agree?”

“I saw her—she looked ill,” Gwennan repeated, curbing her irritation—and under that the birth of suspicion—could he possibly be right? She had wondered more than once concerning the reason for her acceptance at Lyle House. Had that really been part of a game? No, she refused to believe him.

“Naturally. Saris is also an actress of skill—”

Gwennan stopped short, half swung around to face him. “I do not know what you want—why you are telling me all this. If you believe that I am no longer welcome at Lyle House as far as your aunt is concerned, then why do you urge me to still come? What is behind this—?”

Though that shadowy smile never left his lips she was certain that there was a glint of what might be annoyance, even ang

er deep in those gem hard eyes. At their first meeting she had seen them appear unnaturally bright, flashing—but this late afternoon they had dulled close to the shadow of winter ice, and, in their own way, they were as cold.

“You wish a moment of truth. Very well—I have been attempting to spare you distress because I—well, I find you interesting. In this dull town very little is. You have another life—a hidden one, I believe—under that prickly coat you cling to. My dear aunt is a person, as I have stated, of sudden enthusiasms especially concerning people. She becomes quickly bored—especially when she has to camp out in this back-of-beyond family tomb. That’s what Lyle House really is, you know, a mausoleum of the Lyles, simply a piece of turgid history in which no one can be remotely interested any more. She found you of aid in reducing her boredom. But you are nothing more than that to her—a matter of passing amusement.

“On the other hand, I—”

Gwennan continued to stare at him. “I am not interested. I have said that before, I say it again and maybe this time you will believe it. You have made your offer—do you also need a panacea for boredom at present, Mr. Lyle? I have refused it. Now I think that we have nothing more to say to each other. If you will excuse me—”

She would have started on but he flung out an arm as a barrier.

“You can’t—” Here was a breakthrough of something which was on the verge of concern, something she felt was entirely strange in their interview.

“I what?” Gwennan’s irritation could no longer be contained. “Mr. Lyle, I do not in the least understand why you want to continue this conversation. We simply have nothing more to say to each other.”

There was no mockery in his expression now. His lids drooped a little so she could not see the full coldness of his eyes. It was almost as if he were thinking swiftly and forcefully that he needed to find words which had meaning—at least to him.

His other hand had raised to near on a level with her eyes. Now a finger of that moved. She felt a flash of sudden giddiness, nearly as sharp as that which had assaulted her when she had won away from the regard of the eyes during the storm. Her anger blazed and she brought up both her mittened hands, palms out, thrusting away the arm he still held to bar her. At the same time there came a sharp pain in her head—almost as if something had burst there, breaking outward, struggling to be free.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

Space Service Perilous Dreams

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

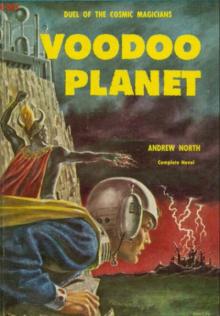

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

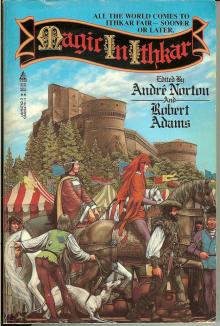

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1