- Home

- Andre Norton

Sword Is Drawn Page 8

Sword Is Drawn Read online

Page 8

As Lorens approached the gate, a sentry swung up his rifle and challenged.

“Capt. Piet van Norreys” — Lorens leaned a little heavily on his own weapon — “is he here?”

It was a Eurasian officer coming up behind the soldier who answered.

“Capt. van Norreys is no longer here — ”

The officer’s face became a smudged blur, then sharpened into proper focus again. Lorens reached out a hand and steadied himself against the post. He couldn’t really remember when he had last eaten a full meal, and the night before he had spent in uneasy napping on a straw sleeping mat in a native kampong. Now here he was, but Piet was gone again.

“Where did he go? When?” he asked dully.

“He left yesterday. We have had orders to clear the fields. That was the last of the bombers taking off from here — ”

“You mean that they were leaving Java — those planes?”

“They are. Those that can leave. This is the end.” The officer’s short sentences, spoken in an emotionless monotone, were like a blow in the face. This was a man who no longer had any hope for the future. “All over the island those which can still fly are ordered out. Capt. van Norreys went to Tjima to see about evacuating the ground personnel — some American and British ships are still there.”

“And where is Tjima?” asked Lorens.

The officer unfolded a thumb-marked square of paper. “It is on the south coast — here. A small fishing port. Do not follow the road too closely, they have bombed and machine-gunned it twice since noon.” He put the map back in his shirt pocket. “We shall do what is to be done here and then we’re going up.” He jerked his thumb toward the mountains. With no other word of farewell, he started back to his waiting men. Lorens lingered. He was finding it increasingly hard to think clearly, just as he could no longer keep any track of time.

What should he do now? Try once more to catch up with Piet at this Tjima, or go with the group who were planning to return and join the forces still resisting in the mountains? To go back would mean fighting and meeting the end in some last desperate struggle among the terraced fields. If he reached Tjima and found Piet, he might be of some help to him and the air force his cousin was trying to save. Which way should he go — ?

He slung his rifle over his shoulder by its strap and dug his hands deep into the pockets of his ragged slacks. In the left one was his handkerchief with the little knob of rubies knotted in the corner. He took them out to look at again, the dull grayish stones. Then he picked out the largest one.

“If it lands up the road I go to the mountains,” he said aloud. “Down the road, I’ll try to reach Tjima. Here goes!” Closing his eyes he tossed the stone into the air.

“It went over there, Tuan.” The sentry, who had been watching with interest, pointed just as Lorens opened his eyes. “That is it, is it not?” The speck of gray he had seen in the brown clay was ‘it’. Lorens picked it up, then, on impulse, he turned and flipped it onto the side brim of the sentry’s hat.

“Take care of that,” he suggested. “It’s a ruby. And good luck to you, comrade.”

He shuffled off before the open-mouthed soldier could frame a reply, following the road down the slope of ground toward the unknown Tjima.

Within a quarter of an hour he had overtaken his first refugees, a family party of four — grandmother, mother, and two small sons — lumpy bundles slung on the shoulders of even the smallest, trudging toward the coast. Father and eldest son, the mother said in answer to Lorens’ questioning, were serving with the Landstorm — where, she did not know. They were going to her sister for shelter since their own kampong had been bombed at sunset the day before.

Lorens stayed with them until they stopped beside a pool for evening rice, carrying the largest bundle, and refusing the offered portion of their scanty food. But his impatience would not allow him to linger when they halted, and he hurried away to be caught up in the stream of refugees heading seaward.

It was after dark that he came to a lorry off the road with a group of Anzacs sweating to get it out of the liquid glue of the rice paddy and back on solid surface. When the sergeant in charge discovered that Lorens could speak the native dialect as well as English, he calmly commandeered him to translate the instructions he had been trying, by the force of shouting and gesturing, to give to the original lorry crew.

But even the sergeant was forced to realize the impossibility of his task when the hub caps of the big wheels were lost to view. Undaunted, he ordered his own men and the natives to unload the stranded and sinking machine and take all they could carry of the supplies.

Lorens traded his flashlight with its almost dead batteries for a new one of British army issue, crammed sticky chocolate into his mouth and a package of iron rations into his shirt, ending by filling his pockets with rifle cartridges, all from the boxes the sergeant had ordered broken open. What they must leave was hurled into the rice padddy to be hidden from sight in the slimy mud. The sergeant then formed up his squad and marched them on, the Javanese drivers, now armed and well equipped, bringing up the rear. Lorens matched steps with the sergeant, trying to answer his questions and ask a few of his own.

Nobody, the Netherlander discovered, seemed to have a very clear idea of what was happening to the Indies. Singapore had fallen, Burma was gone, or going fast, with a disorganized Allied Army and a starving Chinese force trying to fall back into India. Sumatra was gone. They were yet resisting in Borneo. But for Java, caught in the pincers of occupied Sumatra and Bali, there was no hope left.

“It’s this way, chum” — the Anzac explained his own part in the rout — “the last orders I had were to take that blamed lorry through with supplies for the boys who are to hold Tjima. Well, you saw what happened to the lorry. Wha’d’y expect, trying to run these roads at night without lights? We’ll get to Tjima on our own two feet and bring in what we can pack.”

“Then it is planned to make a stand at Tjima?”

“How do I know? How does any man know what’s going to happen in this here war? Japs are landing by parachute all over the place — to say nothing of those moving in from Palembang. Though they ain’t going to get the oil they was after there. Cruel hard what happened, sand and grit thrown into them going engines, blowing up the wells, and all. But here — well, our crates are bombed into splinters before they can take off, we’re flying old traps held together with baling wire now.

“And you can’t hold a country when they keep dropping men behind your lines and cutting into you from the rear. We was caught just thinkin’ when we shoulda been doin’ again. Now I’m going to think a little for this outfit. We’re movin’ into Tjima, and if we can’t find someone to tell us where th’ rest of th’ outfit is, we’ll move out again! There’s some mighty good Jap huntin’ to be done back in th’ hills!”

Lorens found his body settling into the marching rhythm set by the sergeant and the men behind him. He had been tired, but that was hours ago. Now he felt nothing but a sort of prickling excitement, an overwhelming interest in what was going to happen next. Across the night they could see the blaze of the oil fires, of factories, shipyards, warehouses, feeding black smoke to the clouds. Powdery soot and ashes drifted through the air.

“You Dutch are cleaning it up all right,” commented the sergeant.

“For a year, maybe more, they will be able to get nothing from this land,” returned Lorens. “We had our plans made long ago — ”

“A cruel shame, chum. We was on th’ Musi when they was burnin’ th’ fields and refineries there — a good job, too right. So hot it was we could feel it clear across th’ river, and that’s a half mile. It ain’t right; a man builds up a nice business of his own and then some Jap or Nasty smashes it flat — or else he has to burn it up hisself. That’s grim hard, it is. You come from hereabouts?”

“No. I am from the Netherlands. I have been here only since last year. My cousin is the owner of the Singapore-Java Airline. And you are from Austr

alia?”

“Too right. Come from Grafton in New South Wales. Proper town that — near Sydney. This war sure mixes us up — here’s you from Holland, and me from Grafton, and yesterday I met a Yank from some town in one of their eastern states, Cleveland, Ohio, he called it. And he had a chum who was part American Indian, both of them flyers. Then their head mechanic was a Chinese and his assistant was a Scot from Aberdeen.”

“It does not matter who fights at your side if he fights for your cause — ”

“True that. Me, I’ve been in Egypt, and Greece, so far in this war, and my brother’s in Burma — he’ll probably land up in India — trust Bert to get hisself out of trouble. And who knows where we’ll all be when th’ mess is over. I’m rather hopin’ I’ll be seein’ Berlin, or else Tokyo. If there’ll be enough of it left to see. These yellow chaps may think they have us runnin’ now, but a slow start makes a strong finish. Jim,” he called over his shoulder, “pass th’ word down to one of them Java boys, I want to make sure we’re still headin’ direct for Tjima.”

The Javanese assured him, via Lorens’ translation, that Tjima was before them and that they ought to come into the town well before sunrise.

“There” — he pointed to a column of flame — “is the oil refinery of Tuan Umbgrove — to the east lies Tjima.”

Umbgrove, Lorens tried to place the name. Yes, Piet had spoken of Hendrik Umbgrove, the oil man — Umbgrove — why, it was the American girl, Carla Cortlandt, who had mentioned staying with the Umbgroves. What had happened to her, he wondered. Surely she had left the Islands before this, her father would see to that.

Maybe she was well on her way home across the Pacific — home to a country where the lights still dared to show in night-clad cities, where no raiders droned down the wind to drop their blasting burdens of death.

“Halt!”

The Anzac sergeant may not have understood that Dutch order, but the urgency in it made his own voice crack in the British equivalent.

“Who are you?” Lorens automatically demanded of a figure half seen against the fire glow of the sky.

“Landstorm. And what are you?”

“This is a British supply force ordered through to Tjima,” replied Lorens. “And I am trying to join my superior there — Capt. van Norreys of the Air Force.”

A pencil of light marked out his face, then switched to the sergeant and his men.

“All right. Keep on this road. There will be other out-posts before you reach the town. Better get in as quickly as possible, there have been more Jap paratroopers reported landing in the west.”

Lorens translated, and the sergeant nodded. “Good-oh, we’ll push along now.”

And push along they did, at a pace which reminded Lorens that he had feet. Open fields stretched on either side of their road, and the glow from the fires made it light enough to see small parties of men marching determindedly back toward the hills.

“Looks as if we’re plannin’ to hold. Those chaps better get under cover before some Jap plane spots ‘em. Step it up back there, Jim, we’re goin’ to find out just where we’re needed most!”

Tjima lay in a round cup of which a harbor reef made half the rim. A year before, it had been a sleepy fishing village. Six months before, it had been a suddenly important supply port. And now it was a crazy madhouse of activity, sound, and misery. As for finding one man in that throng of stricken refugees, hurrying squads of soldiers, and milling townsfolk, that was almost an impossible task, Lorens decided, after one look into the muddle where men in uniform were still trying to preserve order in spite of growing spurts of panic.

He parted abruptly with the sergeant when the latter saw and started to trail the khaki of a British army jacket, his obedient squad at his heels. But Lorens kept on, pushing through the crowd to be washed up on the steps of what was Tjima’s leading hotel.

And those steps were not empty. He had to edge his way among bodies flaccid with sleep, step over hastily knotted bundles and those treasures snatched up by a people trained in peace and suddenly made homeless by war. A gamecock made choked noises in its throat from the top of a willow basket, and a child held out a brown palm on which lay some grains of rice to comfort it.

The lobby was just as packed with careless sleepers who occupied the chairs, the tables, the floor, leaving free only a very narrow path to the desk. Lorens made his way toward that post of information. It did not help his self-confidence any to catch a glimpse of himself in one of the full-length mirrors. After one blink at that battered scarecrow which seemed to be his reflection, he averted his eyes hastily.

“Capt. van Norreys” — the Javanese desk clerk echoed the name. “But, yes, he was here only this morning, Tuan. He was getting men and supplies on board a tanker which was supposed to sail two hours ago. Where he is now” — the young man flung up his hands in an expressive gesture — “who can say? No one can longer keep account of anyone in Tjima. Just look, Tuan, at these sleeping here. And in each room we have five, six, even ten! Tjima has gone mad!”

“Did he leave a message?” Lorens leaned heavily against the edge of the desk. “I am his cousin, Lorens van Norreys.”

“Wait but a moment, Tuan.” The clerk reached in a desk drawer and pulled out a great bundle of bits of paper, some torn and stained. These he flicked through with the ease of much practice. At one he hesitated, read the superscription again, then pulled it out with an air of quiet triumph.

“There is, as you say, Tuan, a message for you.”

Lorens tore open the envelope and read the lines scrawled across the half sheet.

“ ‘Very important you come Quing Sak’s bazaar at once.’ ” There was no signature, but the envelope was addressed plainly to Van Norreys, and only Piet would be expecting him.

By following the clerk’s directions he was able to find Quing Sak’s bazaar, a sprawling Chinese store on a side street. Its doors were shut, and probably barred, and every window shutter was firmly in place. Lorens knocked loudly.

“Who there?” demanded a voice in the pidgin language of the traders.

“Van Norreys.” Lorens could hear the sound of a bar being withdrawn, then the door was held open just enough for him to squeeze through.

The room was mostly in darkness, only the tiny oil lamp in the hand of its owner made any fight against the gloom. The old Chinese who held the light close to Lorens’ face was wearing a full robe of dark silk above which his shrunken face was as wrinkled as the hull of a nut. But there was nothing aged about his eyes.

“You come ’longside Quing,” he ordered and shuffled away down the long room, Lorens at his heels.

The bazaar must have been larger than it seemed from the outside, for they went through several dark rooms before they came to a last windowless box where a large old-fashioned oil lamp banished shadows to the corners.

“He come now,” Quing informed the two figures by the table.

“But this is not — !”

“Mijnheer van Norreys!”

The two exclamations crossed, and Lorens added one of his own, “ Juffvrouw Cortlandt!”

For it was really she who had risen to her feet and stood staring at him.

“But we were waiting for Capt. van Norreys,” she faltered.

“We?” His gaze swung to her companion.

Hu Shan had lost none of his sleekness. He was the same picture of well-to-do merchant who had padded down the halls of that old house in Batavia. And now, catching Lorens’ attention, he tucked his hands into his long sleeves and bowed in formal politeness.

“But — what is this all about? What are you doing here, Juffvrouw, and — ”

“Please.” Hu Shan raised his hand. “Sit and rest yourself, Mijnheer, and I shall endeavor to explain. It is this way, when all Americans were being evacuated from the island, Juffvrouw Cortlandt chose to remain because she believed that her father would return to search for her, and if she were not here, he would not give up such a search and escape.”

>

“So— so” — Carla took up the tale — “I— well, I hid. The Umbgoves thought I had gone, and the Consul thought I was with them. Then the Umbgoves did go, and when I went back to their house there was a message from Dad telling me to get on to Sydney and that he’d meet me there. I didn’t know what to do, except try to reach the nearest port where there might be a ship. Then I found that the Japanese had cut through and we were surrounded — ”

“It was at that time” — Hu Shan’s smooth voice took over — “that I most literally stumbled over the Juffvrouw and was able to offer her aid in reaching here. We attempted to get in touch with Capt. van Norreys, since for a time he seemed to be in charge of evacuation here. But he left some hours ago and now we do not know where he is — ”

“Have you tried to get passage on one of the freighters?” asked Lorens.

Carla was still able to smile, but it was a rueful one. “Have you?” she countered. “You cannot get within a block of the ticket office or near the docks. And most of the space is being used for vital supplies and men.”

“There is one other chance,” Hu Shan said. “We are awaiting news of that now, Mijnheer — ”

“Are you leaving, too?” Lorens demanded bluntly of the Chinese.

“I? No, Mijnheer. I am remaining. There is yet work to be done.”

“Work? What kind of work — ”

“Would keep a Chinese in reach of his enemies?” Hu Shan caught up and finished Lorens’ question. “The same kind of work for my country, Mijnheer, that you are prepared to do for yours. You see, the brown monkey people believe that some of us — to save our cash and the skins on our back — will do as they order. And some of us — may they eternally walk the Seven Hells! — do. But a man can take service where his heart is not, and that is what I have done.

“In this land I am a pair of eyes and ears for others. To the monkey ones I supply misinformation, to those in Chungking that which is true. So it becomes my duty to remain and welcome the triumphant conquerors, doubtless I shall discover it a most educational experience. While it is your duty to go and fight for yours.” He raised his hand in sudden warning, for old Quing had returned to spit out a stream of gutturals from the doorway.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

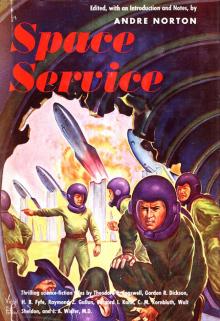

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

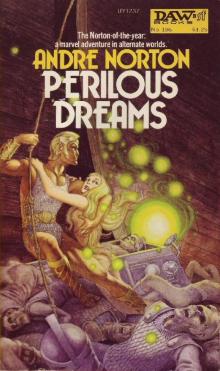

Space Service Perilous Dreams

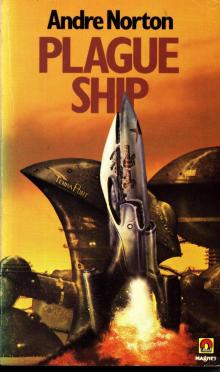

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

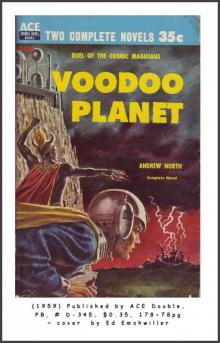

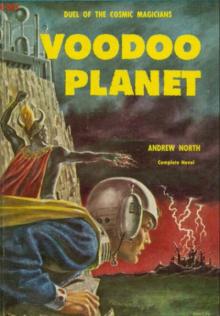

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

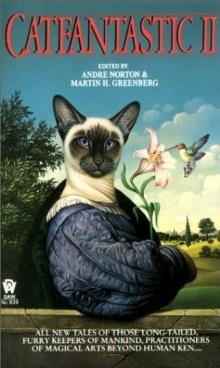

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

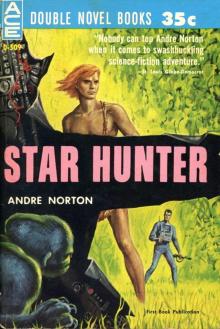

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

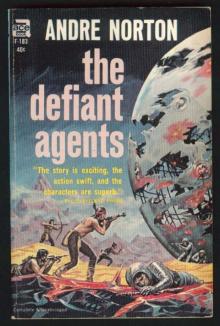

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

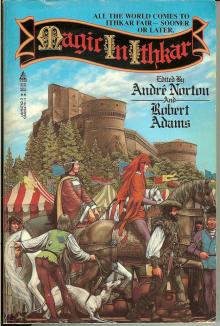

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1