- Home

- Andre Norton

Murders for Sale Page 9

Murders for Sale Read online

Page 9

“It’s—it’s Miss Wing at the Hartwell bookshop.”

“Oh yes, Miss Wing.” He hesitated. Suspicion had now become solicitude. “Are you quite sure nothing’s wrong? Well then—”

In the end he gave her Thane Carey’s number and she put it beside the telephone. Then, feeling both virtuous and courageous, she went upstairs, took one of Dr. Scott’s pills and went immediately to sleep.

When Fredericka woke the morning was fresh and cooler after the rain of the day before. The sun sparkled brightly on the wet green grass when she slipped out on to her back porch to look for signs of her marauder and to sniff the air. The path was trampled with footsteps of all sizes and shapes—yesterday’s rain and yesterday’s visitors had churned the brown earth and flattened the grass. No, there was no evidence. But even in the bright light of day, Fredericka knew that she had not been dreaming. And she was more than ever convinced that her visitor had been Margie. She thought of this as she was cooking and eating her breakfast, and then her mind travelled backwards to the problems that had become crystal clear by the simple process of writing down, as she had in her last night’s letter to Miss Hartwell, the significant events since her arrival in South Sutton.

As she poured out her coffee and made her toast she thought of this letter and what she had said, and then, inevitably, that she must get it off. She hadn’t bothered with a stamp last night. She’d have to find one and then get Christopher to take it to the post office. If only he would put in his appearance. Why hadn’t he come yesterday? During the first week, she had put him on to full time. Surely he understood this. She had expected him all morning and then, when the afternoon’s visitors had started to appear, she had forgotten him completely. Now, thinking of him, she remembered his perspiring black face as it emerged from the bushes that first afternoon when she had been lying in the hammock. Had there been something sinister about that face? Certainly the events of these last few days were enough to make anyone uneasy and suspicious without cause. Could it have been Chris last night? Of course not. But why hadn’t he come yesterday?

As if in answer to her question, there was a loud knock on the back door. Startled, and annoyed with herself for being startled, Fredericka got up quickly and went out. Christopher stood on the porch, turning his battered straw hat in his workworn brown hands. He smiled disarmingly and Fredericka’s nightmare vanished.

“Fixin’ to come yist’dy, but found it advisable to help out at the depot with a parcel o’ freight for Miss Philippine.”

“But that didn’t take all day, did it?”

“No ma’am, Miss Wing. But I then went out to the Farm where I busy myself with one business and then another business. Did reckon to come along here afterwards, but they wasn’t no time lef’, time I got done.”

“But Christopher, I thought you were going to be regularly employed by me now. Wasn’t that what we agreed? I mean, I thought you were my man.”

“Yes, ma’am—but the good Lord He say we is to help one anothers and as they done have all this trouble…” He stopped and then added significantly, “Mis’ Hartwell, she never used to mind much.”

“I see.” Fredericka bit her lip in annoyance, but she knew it would be both unwise and quite useless to say more. “I have some coffee for you,” she said quickly.

Christopher’s grin returned and he nodded vigorously. “I’ll jes’ set myself down on the porch here for the time bein’. Mis’ Hartwell she don’t like my boots for outside to go inside on her floors.” He exhibited a pair of muddy shoes heavily studded with nails. As Fredericka turned to go in to the kitchen, she looked back and saw with surprise that Christopher had glanced furtively over his shoulder and then walked to the far end of the porch.

Was everyone queer, or was there something wrong with herself? Fredericka poured out the coffee quickly and took two doughnuts from Miss Hartwell’s large crock. When she got back to the porch she found Christopher sitting on the far edge with his feet stretched out before him. He seemed to have shrunk down into his bright plaid shirt, and to be regarding his outdoor boots with deep concentration.

“What’s the matter, Chris?” she asked, feeling sudden anxiety for the man.

He took the coffee with obvious gratitude, but did not reply. And all at once, Fredericka knew the answer. Christopher was frightened—plain frightened. That was why he had to get himself as far away from the hammock side of the house as possible. No doubt that was why he hadn’t appeared yesterday.

“It’s all right, Chris,” she said quickly. “They’ve taken the—er—I mean they’ve taken Mrs. Clay—and the hammock away.”

“Yes, ma’am,” was all Christopher said, but his look of relief was obvious. He began to dunk his doughnut in his coffee with every appearance of complete satisfaction.

Was it simply superstitious fear or was it a sense of guilt? How much did he know about Margie Hartwell’s secret hiding place?

“Chris,” she said suddenly, “I was looking about the place on Sunday and I discovered a break in the fence. Did you know about that?”

“Jes’ an ole foxhole, I reckon. I told Miss Lucy and she say she ain’t worried about no foxes round here.” He laughed and the sound grated unpleasantly on Fredericka’s oversensitive nerves.

“Well, what about that collection of things in the old greenhouse back there?”

“Those belongs to Miss Margie. Miss Lucy, she say they is not to be removed.” He frowned down at his empty coffee cup.

It’s a conspiracy against me, Fredericka thought unreasonably. Well, it was no use trying to get anything more out of Chris. She took the coffee cup and went to get the letter to Miss Hartwell.

In searching for a stamp in the desk drawer, Fredericka saw the little silver patch box, and her mind strayed for a moment from her immediate purpose. She could have asked James Brewster if he had observed anyone using it. Perhaps Peter had been serious after all. But surely the box must belong to Margie. It had been found near the porch and it was Margie who used the back way more than anyone else. But it was true that the box didn’t look in the least like Margie. It looked more like—yes, of course, like Catherine Clay herself. Catherine probably did come around to try the back door when she found the front locked on that fateful Saturday afternoon. And it was a fact that she had come part way around since she would have had to in order to get into the hammock. If only she had asked James, he would have known whether or not it was Catherine’s and his reactions would have been interesting—very. Well, she wasn’t much of a sleuth.

Fredericka put the box back into the drawer with a gesture of impatience. What would happen to her work if she spent all her time in idle speculations that came to nothing? She found a stamp, stuck it on the letter with unnecessary force, and went back to Christopher.

“I don’t know when the mail goes, Chris, but will you please take this for me? Don’t make a special trip but I would like it to go out today.”

“Yes ma’am. I was fixin’ to cut this here grass, and straighten out the contents of the stockroom. Mail don’t go nohow this forenoon. Reckon I can take it when I go for the mail round about twelve o’clock.”

“Good.” Fredericka turned to go back into the house when Chris spoke again.

“I’ve been thinking further about that ole well. It do make me worry some, all open like it am. I put an ole box cover over it like but it’s not much use. Sam Lewis is doin’ a job down the road. I could jes’ ax him to come by and have a look at it.”

“I’ve written to Miss Hartwell, Chris. We ought to have an answer in a few days. Don’t you think we can get along until we hear? I don’t really like to involve Miss Hartwell in expense unless I’m sure she wants me to.”

“Yes, ma’am, O.K. then.” Chris now put his dilapidated hat on his head with an age-old gesture of resignation and loped off through the jungle path. Fredericka returned to her dishes and then to her desk, and, after a few moments, was relieved to hear the clanking whir of the lawn mower. He see

ms to be doing the side lawn, she thought. So he must have recovered from his panic. That was one good thing.

She continued to work steadily but some impulse made her get up and go to the window when the lawn mower stopped suddenly. Between the two trees where the hammock had hung, Chris was down on his hands and knees. Praying? Fredericka asked herself. Surely not. She was about to go to the door and investigate when Chris got to his feet and returned to the lawn mower. I must pull myself together, Fredericka decided. There is no doubt whatever that he was trimming the grass around the trees—

After this interruption, the morning passed uneventfully except for a telephone call from Thane Carey who had received the sergeant’s report. She told him briefly of her adventure and he questioned her closely. Then he said that he was on his way out to the Farm and would, himself, question Margie. He sounded abrupt and hurried and after a few brief pleasantries, he hung up. Well, he doesn’t seem to be much alarmed, Fredericka decided as she returned to her desk. Thank heaven I didn’t get him out of bed in the middle of the night.

Two or three customers came to return books to the lending library and lingered to ask the inevitable questions. But Fredericka despatched them quickly, having now learned a satisfactory technique for dealing with them. Each time she remembered the little silver box, but none of her visitors had ever seen it before. They looked at it with undisguised interest, however. “Better put up a notice in the post office,” one of them suggested.

“I will if all else fails,” Fredericka said, slipping the box back into its drawer.

She was still working at the pile of bills and orders on her desk when she was aware that someone had come in behind her. She turned quickly to see Chris standing in the doorway.

“What is it?” she asked, trying to keep the fright and annoyance from her voice. Why did he have to creep so? “I thought Miss Hartwell didn’t like you coming in the house with your boots on,” she added severely.

“I took them off, Ma’am, Miss Wing.” He handed her a pile of letters. Fredericka looked down at his stockinged feet and one large protruding toe, and was ashamed of her outburst.

“Thanks, Chris.”

When he did not at once depart, she looked up at him.

“I saw you had a stamp there from foreign parts—” He coughed. ‘France.’ Then, in a rush, he added, “Miss Hartwell very kindly give me such stamps for my collection.”

“Of course, Chris.” She tore open the letter carefully and cut out the stamp.

Chris took it and stared at it for a moment. “Miss Catherine she got one jes’ the same as this here one. But she won’t be there. No ma’am. Bein’ as how she am dead,” he added lugubriously.

“No. You take the Farm mail too?” Why all this service to the Farm? And why am I so unnaturally curious? she asked herself.

“Yes, ma’am. I am, as yo’all might say, the postman hereabouts and the freight man and the general handyman, as it were.”

“I see. Then I don’t wonder you collect stamps,” Fredericka said a little absently. She wished now that he would go and let her get on with her work.

At this moment, the back door banged and Margie burst into the room.

“Have you got the Farm mail, Chris?” she asked without so much as a glance at Fredericka. “I’m just going back—”

Chris handed her the letters with a look of disappointment. It was obvious that he would have liked to have personally delivered the letter addressed to Mrs. Clay. His departure was slow and dignified.

Margie flopped down into the big chair and thumbed through the letters. Fredericka, who had had more than enough of Margie, started to express her feelings when she was saved by the appearance of an old lady with a book for the lending library. Fredericka went across the hall with her and soon learned that her customer was Mrs. Pike, and that she had made the quilt which Fredericka had won at the bazaar. Fredericka would normally have been interested in this fact and in the long and detailed story of how the pattern had evolved but she had Margie very much on her mind. Should she ask her about last night or leave that to Thane Carey? The girl had seemed so preoccupied and tense.

Then, in the middle of pink against blue or red against green, Fredericka suddenly remembered that she must ask Margie about the silver box. She made some excuse and the old lady turned rather huffily to the shelves. Fredericka hurried back to the office to find Margie gone, and the desk drawer half-open. She looked inside quickly and was relieved to find the box there, just as she had left it. Perhaps she had, herself, forgotten to shut the drawer properly. She took out the box and, without bothering to make further excuses to her customer, dashed out the back way. She ran all the way to the gate into the alley which she found standing open. But there was no sign of Margie.

“Plague take her,” Fredericka muttered as she hurried back to the shop and her fretting client.

For the rest of the day Fredericka was too busy with customers to think of anything else. She ate only a sandwich for lunch and a chocolate milk shake that Chris brought back to her when he took his wheelbarrow to the station to collect freight parcels in the afternoon. He trundled the barrow in by the front gate and around the side path to the back porch where Fredericka stepped out to meet him. The paper carton of milk shake was poised precariously on top of the bundles of books like a lookout on a craggy mountain. Chris handed it to her solemnly.

“Everyone in this town is talkin’ like they was murder crimated in this place,” he said heavily.

“Nonsense,” she said a little sharply, and then felt sorry as she took the drink from the large brown hand and looked into the anxious face.

By night, Fredericka was determined to escape from the bookshop and, though she did not admit it, even to herself, she wanted to see Peter Mohun again. Neither he nor Thane Carey had appeared all day and this fact in itself now seemed, to her overwrought mind, to be full of portent. That afternoon a customer had reminded her that there was to be a lecture at the college at eight-thirty. Something about Korea. She hadn’t had a thought of going to it until, after supper, she found herself changing into her best linen dress. Half an hour later, she shut and locked both doors, and departed, hurrying across the campus as though escaping from demons. When she reached the hall she discovered that she was a little late and slipped quietly into a back seat.

The large room was crowded with people, but Fredericka could not see any familiar faces near her. She sat back on her hard chair and looked around at the panelled walls and the row of impressive portraits that circled the room. Certainly the college hall was a far pleasanter place than the church one. Fredericka reflected briefly on the rapid decline of American architecture in the fifty or sixty years from the time this hall had been built around 1825 or 1830 to the church hall, a memorial to the worst that 1880 could do. The lecture was given by a correspondent, recently back from the Korean front and he was introduced by Peter Mohun who seemed abstracted and tired, Fredericka thought. She found it difficult to concentrate—a blue bottle fly buzzed around the light above her and the room grew close and hot. At intervals she dozed but, in spite of this, the time dragged until the sudden stir in the room announced her release. She got up at once and followed the crowd out to the lighted porch where everyone was stopping to gossip and enjoy the soft summer night.

Fredericka stood for a moment, feeling alone in a crowd of strangers. She looked anxiously for Peter but he was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps he had to entertain the speaker. Well, there was nothing for it but to leave. She started slowly across the campus, feeling abandoned, and frightened at the prospect of returning alone to the book-shop, when a hand fell heavily on her shoulder. Startled, she turned to look up into the large red face of James Brewster. Her disappointment was acute.

“The thing to do now,” he announced easily, “is to adjourn to the drug-store for an ice-cream soda. Personally I would prefer something a little stronger but we are in Rome, my dear Fredericka, and so we must be Romans.”

�

��Must we?” Fredericka asked, and meant it.

He took her arm. “We must, at any rate, make a pretence of doing so.”

Fredericka decided that anything would be better than to return alone to her empty house. For this reason, she did not withdraw her arm as she longed to do, and they walked together down the dark street.

“It’s no joke being the Sutton family lawyer,” Brewster said suddenly, but he spoke low and confidingly.

Fredericka who had been avid for news all day was suddenly annoyed. She didn’t want to hear about the Suttons from James Brewster. She didn’t even want to think about them. But James went on without encouragement. “Shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, but really Catherine’s affairs were in a shocking state. Wouldn’t wonder if she had decided to take a quick way out—”

“Whatever do you mean?” Fredericka was now roused to sudden attention.

“Nothing. Oh nothing really, of course. Philippine’s got the family in a much better state with her herb farm. Most remarkable woman. Forget what I said, my dear.” He squeezed her arm affectionately but Fredericka did not even notice. She was thinking of the conversation she had overheard in the inn on her first Sunday and of what Peter had told her of James’s admissions. James Brewster was suggesting that Catherine Clay had committed suicide. How convenient for him if he had indeed switched his affections from the glamorous Catherine to Philippine whom on Sunday he had called “good” and now thought “remarkable.”

“I thought Mrs. Sutton had started the herb business before Philippine came,” Fredericka said quickly.

“Yes, started, but she is old and really quite worn out. It certainly needed someone like Philippine—” He stopped in midsentence and turned toward Fredericka suddenly. She had walked on without noticing that the crowd had thinned: the white dresses had flashed away into the darkness and the chatter of voices and the sound of laughter had become spasmodic and remote. At the moment that James Brewster turned toward her and she felt his hot breath against her face, she knew that they were alone.

Ride Proud, Rebel!

Ride Proud, Rebel! The People of the Crater

The People of the Crater Rebel Spurs

Rebel Spurs The Gifts of Asti

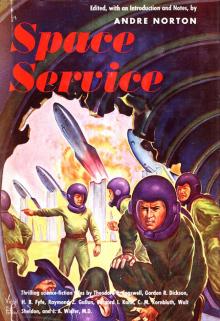

The Gifts of Asti Space Service

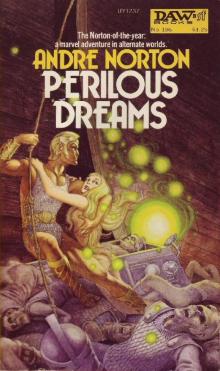

Space Service Perilous Dreams

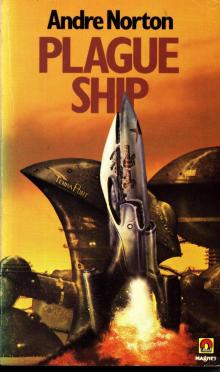

Perilous Dreams Plague Ship

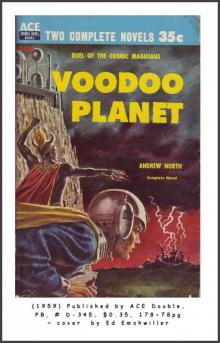

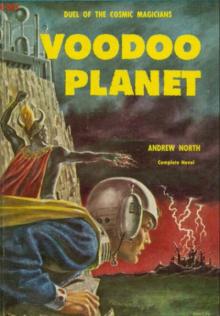

Plague Ship Voodoo Planet

Voodoo Planet Star Born

Star Born The Zero Stone

The Zero Stone Knave of Dreams

Knave of Dreams Five Senses Box Set

Five Senses Box Set The Time Traders

The Time Traders Catfantastic II

Catfantastic II Star Hunter

Star Hunter The Defiant Agents

The Defiant Agents Key Out of Time

Key Out of Time Space Police

Space Police The Monster's Legacy

The Monster's Legacy Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1)

Imperial Lady (Central Asia Series Book 1) All Cats Are Gray

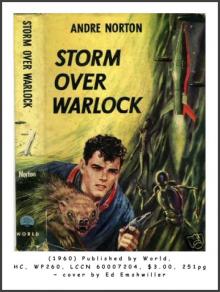

All Cats Are Gray Storm Over Warlock

Storm Over Warlock Warlock

Warlock Firehand

Firehand Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith

Echoes In Time # with Sherwood Smith Ciara's Song

Ciara's Song The Sioux Spaceman

The Sioux Spaceman Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin

Firehand # with Pauline M. Griffin The Forerunner Factor

The Forerunner Factor The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle))

The Jargoon Pard (Witch World Series (High Hallack Cycle)) Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series))

Trey of Swords (Witch World (Estcarp Series)) Children of the Gates

Children of the Gates Atlantis Endgame

Atlantis Endgame Red Hart Magic

Red Hart Magic Steel Magic

Steel Magic Beast Master's Circus

Beast Master's Circus Iron Butterflies

Iron Butterflies At Swords' Points

At Swords' Points The Iron Breed

The Iron Breed A Crown Disowned

A Crown Disowned Moon Called

Moon Called Ralestone Luck

Ralestone Luck Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 3 FORERUNNER FORAY

FORERUNNER FORAY High Sorcery

High Sorcery Stand to Horse

Stand to Horse Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning)

Flight of Vengeance (Witch World: The Turning) Gods and Androids

Gods and Androids Derelict For Trade

Derelict For Trade Ice and Shadow

Ice and Shadow Wraiths of Time

Wraiths of Time Quag Keep

Quag Keep The Scent Of Magic

The Scent Of Magic Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat

Mark of the Cat and Year of the Rat Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning)

Storms of Victory (Witch World: The Turning) Catseye

Catseye The Defiant Agents tt-3

The Defiant Agents tt-3 The Opal-Eyed Fan

The Opal-Eyed Fan Sword Is Drawn

Sword Is Drawn ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE

ORDEAL IN OTHERWHERE Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 1 Wheel of Stars

Wheel of Stars On Wings of Magic

On Wings of Magic Ware Hawk

Ware Hawk The Key of the Keplian

The Key of the Keplian Ride Proud-Rebel

Ride Proud-Rebel Sea Siege

Sea Siege Lost Lands of Witch World

Lost Lands of Witch World Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series)

Horn Crown (Witch World: High Hallack Series) Three Against the Witch World ww-3

Three Against the Witch World ww-3 Wizards’ Worlds

Wizards’ Worlds Secret of the Stars

Secret of the Stars Yankee Privateer

Yankee Privateer Scent of Magic

Scent of Magic Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder

Beast Master's Planet: Omnibus of Beast Master and Lord of Thunder The White Jade Fox

The White Jade Fox Silver May Tarnish

Silver May Tarnish Beast Master's Quest

Beast Master's Quest Knight Or Knave

Knight Or Knave Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series)

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) The Warding of Witch World

The Warding of Witch World Uncharted Stars

Uncharted Stars Ten Mile Treasure

Ten Mile Treasure The Game of Stars and Comets

The Game of Stars and Comets On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning)

On Wings of Magic (Witch World: The Turning) Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2

Tales From High Hallack, Volume 2 The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series)

The Gate of the Cat (Witch World: Estcarp Series) Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk

Andre Norton - Shadow Hawk Merlin's Mirror

Merlin's Mirror Serpent's Tooth

Serpent's Tooth Sword in Sheath

Sword in Sheath Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1

Ride Proud, Rebel! dr-1 The Magestone

The Magestone The Works of Andre Norton (12 books)

The Works of Andre Norton (12 books) Andre Norton: The Essential Collection

Andre Norton: The Essential Collection The Stars Are Ours! a-1

The Stars Are Ours! a-1 Moon Mirror

Moon Mirror Warlock of the Witch World ww-4

Warlock of the Witch World ww-4 Garan the Eternal

Garan the Eternal The Andre Norton Megapack

The Andre Norton Megapack Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4

Dare to Go A-Hunting ft-4 The X Factor

The X Factor Web of the Witch World ww-2

Web of the Witch World ww-2 The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5

The Knight of the Red Beard-The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash and Rowan 5 Star Rangers

Star Rangers Witch World ww-1

Witch World ww-1 Daybreak—2250 A.D.

Daybreak—2250 A.D. Moonsinger

Moonsinger Redline the Stars sq-5

Redline the Stars sq-5 Star Soldiers

Star Soldiers Empire Of The Eagle

Empire Of The Eagle The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1)

The Hands of Lyr (Five Senses Series Book 1) Android at Arms

Android at Arms Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series)

Lore of Witch World (Witch World Collection of Stories) (Witch World Series) Trey of Swords ww-6

Trey of Swords ww-6 Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series))

Gryphon in Glory (Witch World (High Hallack Series)) Octagon Magic

Octagon Magic Dragon Magic

Dragon Magic Three Hands for Scorpio

Three Hands for Scorpio The Prince Commands

The Prince Commands The Beast Master bm-1

The Beast Master bm-1 Shadow Hawk

Shadow Hawk Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World)

Wizard's Worlds: A Short Story Collection (Witch World) Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars

Murdoc Jern #2 - Uncharted Stars Crystal Gryphon

Crystal Gryphon Galactic Derelict tt-2

Galactic Derelict tt-2 Dragon Mage

Dragon Mage Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series)

Spell of the Witch World (Witch World Series) Velvet Shadows

Velvet Shadows Rebel Spurs dr-2

Rebel Spurs dr-2 Space Pioneers

Space Pioneers To The King A Daughter

To The King A Daughter At Swords' Point

At Swords' Point Snow Shadow

Snow Shadow Lavender-Green Magic

Lavender-Green Magic Scarface

Scarface Elveblood hc-2

Elveblood hc-2 Fur Magic

Fur Magic Postmarked the Stars sq-4

Postmarked the Stars sq-4 A Taste of Magic

A Taste of Magic Flight in Yiktor ft-3

Flight in Yiktor ft-3 Golden Trillium

Golden Trillium Murders for Sale

Murders for Sale Time Traders tw-1

Time Traders tw-1 Sargasso of Space sq-1

Sargasso of Space sq-1 Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone

Murdoc Jern #1 - The Zero Stone Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5

Sorceress Of The Witch World ww-5 Time Traders II

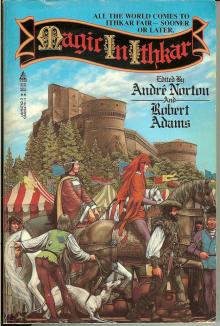

Time Traders II Magic in Ithkar 3

Magic in Ithkar 3 Key Out of Time ttt-4

Key Out of Time ttt-4 Magic in Ithkar

Magic in Ithkar Voodoo Planet vp-1

Voodoo Planet vp-1